March 27, 2019 / gbl08ma / 6 Comments

Many are aware that some YouTubers are unhappy with how YouTube operates. But are you aware that Android app developers go through similar struggles with Google Play? Let me try and explain everything that’s wrong with Android in a single 20 minutes read.

Android was once considered the better choice of mobile platform for those looking for customizability, powerful features such as true multitasking, support for less common use cases, and higher developer freedom. It was the platform of choice in research and education, because not only are the development tools free and cross-platform, Android was also a very flexible operating system that did not get in the way of experimenting with innovative concepts or messing with the hardware we own. This is changing at an increasingly faster pace.

While major new Android versions used to bring features that got both users and developers excited, since a few versions ago, I dread the moment a new Android version is announced and I find myself looking for courage (heh) to look at the changelogs and developer guidelines for it. And new Android versions are not the only things that make my heart beat faster for the wrong reasons: changes to Google Play Store policies are always a fun moment, too.

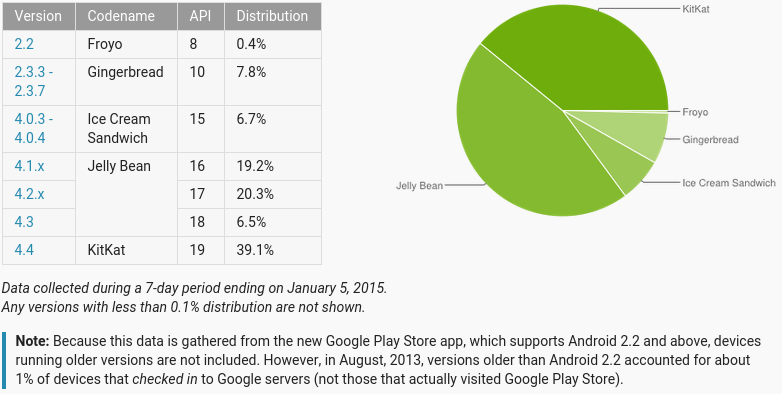

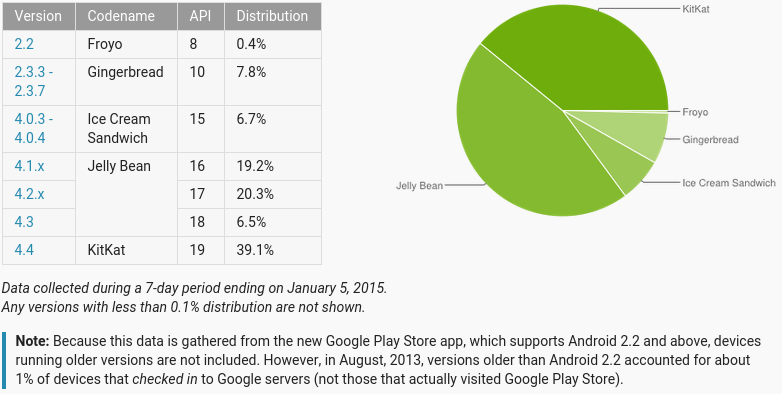

Before we dive in any further, a bit of context: Android was not the first mobile OS I used; references to my experiences and experiments with Windows Mobile 6.x are probably scattered around this blog. I started using Android at a time when 4.2 was the latest version, I remember 4.4 being announced shortly after, and that was the version my first Android phone ran until the end of its useful life. Android was the first, and so far only, mobile operating system for which I got seriously invested in app development.

I started messing with Android app development shortly before 6.0 Marshmallow was released, so I am definitely not an old timer who can say he has seen Android evolve from the beginning, and certainly not from the perspective of a developer. Still, I feel like I have witnessed a decade of changes – in big part, because even during my “Windows Mobile experiments” era, I was paying attention to what was happening on the Android side, with phones I couldn’t yet afford to buy (my Windows Mobile “Pocket PCs” were hand-me-downs). I am fully aware of how bad Android was for both users and developers in the 4.x and earlier eras, in part because I still had the opportunity to use these versions, and in part because my apps had to support some of them.

API deprecation and loss of backwards compatibility

With every Android version, Google makes changes to the Android APIs. These APIs are how apps interact with the operating system, and simplifying things a bit, they pretty much define what apps can and can’t do. On top of this, some APIs require permissions, which you agree to when you install apps that use them, and some of these permissions can be allowed or denied by the user as he runs the app (of course, the app can refuse to run if the permissions are denied, but the idea is that it will degrade gracefully and provide at least some functionality without them). This is the case for the APIs that access your contact list or your location.

New Android versions include new APIs and, in the past, barely any changes were made to APIs introduced in previous versions. This meant that applications designed with an older version in mind would still work fine, and developers did not need to immediately redesign their apps with new versions in mind.

In the past two to three years, new Android versions have also began removing APIs and changing how the existing ones work. For example, applications wishing to stay active in the background now have to display a permanent notification, an idea which sounds good in theory, but the end result is having a handful of permanent notifications in your drawer, one for each application that may need to stay active. For example, I have two in my phone: one for the call recorder, and another for the equalizer system. One of my own apps also needs to have a similar notification in Android 8/Oreo and newer, in order to reliably perform Wi-Fi scans to locate the user in specific locations.

In the upcoming Android version 10/Q, Google intends to restrict even more what apps can do. They are removing the ability for apps to access the clipboard, killing an entire category of clipboard management apps (so that you can have a history of what you copied, so that you can sync the clipboard with your other phones and computers, etc.). Currently, all apps can access the clipboard without special permissions, but the correct way to solve this is to add a permission prompt, not to get rid of the API entirely. Applications can no longer turn the Wi-Fi on or off, which prevents automation apps from e.g. turning off the Wi-Fi when you’re driving. They are thinking of entirely preventing apps from accessing arbitrary files in “external storage” (SD cards and the area of internal memory on your phone where screenshots and camera pictures go, and where you put your MP3s, game ROMs for emulation, etc.).

Note that all of these things that they are removing for “security”, could simply be gated around a permission prompt you’d have to accept, as with the contact list, or location. Instead, they decided to remove the abilities entirely – even if users want these features, apps won’t be able to implement them. Existing apps will probably be review-bombed by users who don’t understand why things no longer work after updating to the shiny new Android version.

These changes to existing APIs mean more for users and developers. Applications that worked fine until now may stop working. Developers will need to update their apps to reflect this, implement less user-friendly workarounds, explanation messages, and so on. This takes time, effort, money etc. which would be better spent actually fixing other issues of the apps, or developing new features. For small teams or solo developers, especially those doing app development as a hobby or as a second job, catching up with Google’s latest “trends” can be insurmountable. For example, the change to disallow background services meant that I spent most of my free time during one summer redesigning the architecture of one of my apps, which in turn introduced new bugs, which had to be diagnosed, corrected, etc., and, in the end, said app still needs to show a notification to work properly in recent Android versions.

There are other ways Google can effectively deprecate APIs and thus limit what applications can do, without releasing new Android versions or having to update phones to them. Google can decide that apps that require certain permissions will no longer be allowed on the Play Store. Most notably, Google recently disallowed the SMS and Call Log permissions, which means that apps that look at the user’s call log or messaging history will no longer be allowed on the store.

Apps using these permissions can still be installed by downloading their APKs directly or by using alternative app stores, but they will no longer be allowed on the Play Store. This effectively means that for many apps, the version on the Play Store no longer contains important functionality. For example, call recorders are no longer able to associate numbers with the recordings, and automation apps can no longer use SMS messages as a trigger for actions. Because Google Play is where 99% of people get their apps, this effectively means functionality requiring these permissions is now disallowed, and won’t be available except to a extremely small minority of users who know how to work around these limitations.

The Google Play Store is the YouTube of app developers

Being on the Play Store is starting to feel much like producing content for YouTube, where policy changes can be sudden and announced without much time in advance. On YouTube, producers always have to be on the lookout for what might get a video demonetized, on top of dealing with content claims, both actions promoted by entirely automated, opaque systems. On the Play Store, we need to be constantly looking out for other things that might suddenly get our app pulled or our developer account banned – together with the accounts of everyone who Google decides has anything to do with us:

And this is just a tiny sample, not even the “best of”, of the horrifying stories that are posted to r/androiddev, every other day. For each of these, there are dozens in the respective “categories”. Sometimes the same stories, or similar ones, also make the rounds in Hacker News. It seems Google is treating Play Store bans and app removals with the same or worse flippancy that online games ban players suspected of cheating. Playing online games isn’t the career of most people who do it, but Android app development is, which leads to the obvious question, what do people do when they are banned?

After writing this, I realize my YouTube analogy is terrible. You see, on YouTube generally one receives strikes, instead of waking up one day to suddenly see their account banned. YouTubers also have the opportunity to profit from the drama caused by the policy changes by “reacting” to them, for example. And while YouTubers typically have the sympathy of their viewers, app developers have to deal with user outrage – because users have no idea, or don’t care, about why we’re being forced to massively degrade the performance and features of our apps. For example, the developer of ACR, a popular call recorder, had to deal with bad app reviews, abuse and profanity among thousands of emails from outraged users after removing the call log permission, and this was after an extensive campaign warning users of the upcoming changes (as a user of ACR, I uninstalled the Play Store version and installed the “unchained” version, which keeps the call log features, through XDA Labs).

As a freelance developer or as a small company, developing for Android is riskier than ever. I can start working on an app idea today and it’s possible that in six months, when it is ready for the initial release, changes to the store policy will have rendered my app unpublishable or have severely affected its functionality… in addition to the aforementioned point about APIs deprecating and changing semantics, requiring constant upkeep of the code to keep up with the latest versions.

If you opened the links above, by now you have probably realized another thing: user support with actual humans is non-existent, and if only their bots were as responsive as Google Assistant… And, if they are not bots, then they are humans which only spit out canned responses, which is just as bad. It is widely known that the best method for getting problems solved with regards to Google Play listings, is to catch the attention of a Google employee on social media.

It seems the level of support Google gives you is correlated to how many people will read your rants about your problems with their platforms. And it’s an exponential correlation, because being big isn’t enough to get a moderate level of support; you must be giant. This is a recurring problem with most Google services, especially if you are not using G Suite (apparently, app developers do not count as “paying customers” when it comes to support). Of all the things I’d like the EU to regulate (and especially, to not regulate, but that’s a story for a different time), the obligation for these mega-corporations to provide actual user support is definitely one of them.

Going back to the probably flawed YouTube analogy, there’s one more parallel to draw: many people believe that in recent years, YouTube has been making changes to both policies, business models and the “algorithm”, that heavily favor the big, already-established creators and make it hard for smaller ones to ever be successful. I believe we are seeing a similar trend on the Google Play Store – just keep in mind you must not analyze an app’s popularity or “level of establishment” by the number of downloads or active users, but by how much profit it generates in ad revenue and IAP cuts.

“Android is open source”

“Android is open source” is the joke of the year – for the fifth consecutive year. While it is true that the Android Open Source Project (AOSP) is still a thing, many of the components that make Android recognizable and usable, both from an end user and developer’s perspective, are increasingly closed source.

Apps made by Google are able to do things third-party apps have trouble replicating, no doubt due to the tight-knit interaction between them and the proprietary behemoth that is Google Play Services. This is especially noticeable in the “Google” app itself, Google Assistant, and the Google launcher.

If you install an AOSP build, many things will be missing and many apps – my own ones included – will have trouble running. Projects looking to provide “de-googlified” versions of Android have developed extensive open source replacements for many of the functions provided by Google Play Services. The fact that these replacements had to be community-developed, and the fact that they are very much necessary to run the majority of the popular applications, show that nowadays, Android can be considered open source as much as in the sense that it can be considered a Linux distro.

AOSP, on its own, is effectively controlled by Google. The existence of AOSP is important, if nothing else, to define common APIs that the different “OEM flavors” of Android must support – ensuring, with minor caveats, that we can develop for Android and not for “Samsung’s Android” or “Nokia’s Android”. But what APIs come and what APIs go is completely decided by Google, and the same is true for the overall system architecture, security model, etc. This means Google can bend AOSP to their will, stripe it of features and move things into proprietary components as much as they want.

Speaking of OEMs and inter-device compatibility, it’s obvious that this push towards implementing important functionality in Google Play Services and making the whole operating system operate around Google’s components has to do with keeping the “OEM flavors” under control. A positive effect for users and developers is that features and security patches become available even on devices that don’t receive OEM updates, or only receive updates for the major Android version they came with, and therefore would never receive the new features in the latest major release. A negative effect is that said changes can affect even old Android versions overnight and completely at Google’s discretion, much like restrictions on what APIs and permissions apps on the Play Store are allowed to use.

Google’s guiding light when it comes to Android openness seems to gravitate towards only opening the Android source as much as necessary for OEMs to make it run on their devices. We are not at that extreme point – mainly because the biggest OEMs have enough leverage to prevent that from happening. I feel that at this point, if Google were able to make Android entirely closed source, they would do it. I wonder what future Fuschia holds for us in this regard.

So secure you can’t use it

The justifications for many of the changes in later Android versions and Google Play policies usually fall into one of two types: “security” and “user experience”, with the latter including “battery life”. I’m not sure for whom Google is designing their “user experience” in recent years, but it certainly isn’t for “proficient users” like me. Let’s, however, talk about security first.

Security should be proportionally strong to what it is protecting. With each major Android version, we see a bigger focus on security; for example, it’s becoming harder and harder to root a phone, short of installing a custom ROM that includes superuser functionality from the start. One might argue this is desirable, but then you notice security and privacy have also been used as the excuse to disallow the use of certain permissions like the call log and messaging access, or to remove APIs including the external storage one.

This increase in security strength makes sense: security is now stronger because we are also storing more valuable information in our phones, from “old-fashioned” personal information about us and our acquaintances, to biometric information like fingerprint, facial and retinal scans. Of course, and this is probably the part Google et al. are most worried about, we’re also storing entire payment systems, the keys for DRM castles, and so on.

Before finishing my point about security, let’s talk a bit about user experience. User experience is another popular excuse for making changes while limiting or altogether removing certain features. If something has to be particularly complicated (or even “insecure”) in order to support the use cases of 1% of the users, it often gets simplified… while the “particularly complicated” or “insecure” system is stripped entirely, leaving the aforementioned 1% with a system that no longer supports their use cases. This doesn’t sound too bad, right? However, if you repeat the process enough times, as Google is bound to do in order to keep releasing new versions of their software (so that their employees can get their bonuses), tying the hands of 1% of the users at a time, you are probably going to be left with something that lets you watch ads only… and probably Google ads at that, I guess. You didn’t need to make phone calls, right? After all, the person on the other side might be pulling a social engineering scheme on you, or something…

Strong security and good user experience are hard to combine together. It seems that permission prompts do not provide sufficient security nor acceptable user experience, because apparently it’s easier to remove the permissions altogether than to let users have a choice.

User choice is what all of this boils down to, really. Android used to give me the choice of being slightly insecure in exchange for having more powerful and innovative features in the apps I install, than in the competing mobile platforms. It used to give me the choice of running 10 apps in the background and having my battery last half a day as a result, but now, if I want to do so, I must deal with 10 ongoing notifications. I used to be able to share files among apps as I do on my desktop, but apparently that is an affront to good security too. I used to be able to log the Wi-Fi networks in my vicinity every minute, but in Android 9 even that was limited to a handful of scans per hour, killing some legitimate use cases including my master’s thesis project in the process. Fortunately, in academia we can just pretend the latest Android version is 8.

Smart cards, including SIM cards, were invented to containerize the secure portion of systems. Authentication, attestation, all that was meant to be done there, such that the bigger system could be less secure and more flexible. Some time in the last two decades, multiple entities decided it was best (maybe it provided “better user experience”?) that important security operations be moved into the application processor, including entire contactless payment systems. Things like SafetyNet were created. My argument in this section goes way beyond rooting, but if my phone is rooted and one of the apps to which I granted root permission steals my banking details, … apparently the banking app shouldn’t have been allowed to run in the first place? Imagine if the online banking of my bank refused to open on my desktop because it knows I know the password for the administrator account.

Still on the topic of security, by limiting what apps distributed on the Play Store are allowed to do and ending support for legitimate use cases, Google ends up encouraging side-loading (direct APK download and installation). This is undesirable from a security point of view, and I don’t think I need to explain why.

Our phones are definitely more secure now, but so much “security” is crippling the use cases of people who do more than binge-watch YouTube and their social network feeds. We should also keep in mind that many people are growing up with smartphones and tablets alone, and “just use your desktop for those advanced tasks” is therefore not an answer. It’s time for my retarded proposal of the week, but what about not storing so much security-sensitive stuff in our phones, so that we don’t need so much security, and thus can actually get back the flexibility and “security pitfalls” we had before? Android, please let me shoot myself in the foot like you used to.

Lack of realistic alternatives

This evolution of Android towards appealing to the masses (or appealing to Google’s definition of what the general public should be allowed to do) would not worry me so much if, as a user, I had a viable mobile OS alternative. On the Apple side, we have iOS, whose appeal from the start was to provide a “it just works”, secure platform, with limited flexibility but equally limited margin for error. Such a platform is actually a godsend for many people, who certainly make up the majority of users, I don’t doubt. Such a platform doesn’t work for me, because as I said, I need to be able to shoot myself in the foot if I want to: let me have 2 hours of battery life if I want, let my own apps spy on my location if I want.

This was fine for many years, because we had Android, which let us do this kind of stuff. It just so happens that because of AOSP, and because there were no other open source or licensable platforms with traction, Android ended up being the de-facto standard for every smartphone that isn’t an Apple one. On the low-end, Android is effectively the only option. Of course, this led to Android having the larger market share. Since “everyone” uses it now, there’s pressure to copy the iOS model of “it just works” and “safe for people with self-harm tendencies” – you can’t hurt yourself even if you wanted.

Efforts to introduce an Android competitor have been laughable, at best. Windows Phone/Windows Mobile failed in part because of a weak and possibly too late entry, combined with a dubious “vision” and bad management decisions on Microsoft’s part. In the end, what Microsoft had was actually good – if there weren’t the case, there wouldn’t be still plenty of die-hard WP/WM fans – but getting there so late (and with so many mixed signals about the future of the platform) means developers were never sufficiently captivated, and without the top 100 apps in there, users won’t find the platform any good, no matter how excellent it is from a technical standpoint. Obviously, it does not help that a significant number of those “top 100 apps” are Google properties; in fact, the only reason Google has their apps on iOS is because, well, iOS was there already when they arrived on the scene.

If even a big player with stupid deep pockets like Microsoft can’t introduce a third mobile platform, the result of smaller-scale attempts like Firefox OS is quite predictable. These smaller attempts have an additional problem, which is finding hardware to run on. It doesn’t help that you can’t change the OS on a phone the same way you can on a PC. In fact, in the long gone year of 2015, I was already ranting about the lack of standardization in smartphone hardware. It’s actually fun to go back at that post, made when Android 4.4 was the latest version, and see how my perception of Android has changed.

I should also note that if a successful Android alternative appears, it will definitely run Android apps, probably through a compatibility layer. In a way, Android set the standard for apps much in the same way that 15 years ago, IE6 was setting web standards in the worst way possible. Did someone say antitrust?

Final thoughts

Android, and therefore Google, set the standard – and the implementation – for what we can and can’t do with a smartphone, except when Apple introduces a major innovation that OEMs and Google are compelled to quickly implement in Android. These days, it seems Apple is stalling a bit in innovation in the smartphone front, so Google is taking the opportunity to “innovate” by making Android more similar to iOS, turning it into a cushioned, limited, kid-safe operating system that ties the hands of developers and proficient users.

Simultaneously, Google is solving the problem of excessive shovelware and even a bit of malware on the Play Store, by adding more automation, being even less open about their actions, and being as deaf as ever. Because it’s hard to understand whether apps are using certain permissions legitimately or not – and because no user shall be trusted to decide that by themselves – useful applications, from call recording tools, to automation, to literally any app that might want to open arbitrary files in the user storage, are being “made impossible” by the deprecation and removal of said permissions and APIs.

We desperately need an Android alternative, but the question of who will develop, use and target said alternative remains unanswered. What I know, is that I no longer feel happy as an Android developer, I no longer feel happy as an Android user, and I’m not likely at all to recommend Android to my friends and family.

Edited at 2:56 March 28th UTC to add clarification about Android clipboard access.

See the discussion for this article on Hacker News, r/AndroidDev, r/Android

April 25, 2018 / gbl08ma / 2 Comments

In the introductory post to this series about the state of internet forums, I mentioned that, to me at least, forums felt like a relic of the past, a medium many internet users will never experience, and that many forums were seeing a downwards trend in the amount of activity in the past few years. But is this just a personal feeling supported by anecdotes, or is this really a general situation?

In the previous post, I also said that these posts would be subjective texts posted to a personal blog, not scientific studies. However, I thought it would be interesting to use these posts to do some introspection and try to understand where this feeling that “forums are dying” comes from. After all, it might just be that I and my circle of friends are abandoning forums, and (in a possibly correlated way) the forums we used to frequent are also dying, while the big picture is quite different. There’s also the possibility that this trend is limited to certain cultures, regions of the world, or specific forum topics/themes.

To do this “introspection”, I’ll be going through some of the forums I know about, and maybe even some I don’t know about, to see how they are doing. I have good news: you can completely skip this lengthy post and you probably will still enjoy the rest of the series. Yeah, this series will still be primarily anecdote-based, but at least we will have looked at a slightly larger number of anecdotes – and we will have taken a deeper look at them. Yay for small sample sizes. Let’s start with the ones I know about.

This forum was founded in April of 2010, and it is the first forum I remember being a part of, although I know for sure I signed up for other forums before that one – also related to web hosting, I just don’t remember their name anymore, and I’m sure that they have not been online for years now. I was one of the first 20 members of that forum, and I ended up being a quite relevant member, because I was a moderator there for over a year, between 2011 and 2012 (or even the start of 2013). I actually got through some “drama” together with the rest of the team, involving forum ownership/administration changes.

I put “drama” in quotes, because to this day I’m still not sure whether the things we were seeing as extremely serious threats were actually that serious… keep in mind that, at the time at least, most of the staff was under 20, perhaps even under 18. I know that at some point legal paperwork was flying around against us, someone wanted to trademark FreeVPS and take the forums from us, or something like that. Now I find all of this a bit cringe-worthy, but I learned quite a lot of stuff (from systems administration, to project management, time management and other soft-skills). Anyway, let’s set the nostalgia aside…

This was actually the first forum I “abandoned”, in the sense I stopped going there as frequently or participating there as much as I initially did. And thus it was only while I was “researching” for this post that I found out that this community, too, is in trouble. The activity levels are way, way down than back in the “golden days”, with what seems to be an average of five posts per day – and sometimes a day goes by without a post. Back in those “golden days”, there would be over 100 posts per day, so much that the statistics page of the forum still indicates an all-time average of 73 posts/day.

This one is not dead, it’s just… trying to find a way to evolve, maybe reinvent itself a bit, in an attempt to bring back the glory of the earlier days. Founded in 2000 – just barely after I learned the basics of how to read Portuguese (let alone write English) – Cemetech (pronounced KE’me’tek) is a community focused on graphing calculators and, to a lesser degree, DIY electronics, and other… nerd stuff. At least, this is how I saw it back when I joined in November 2011. To be fair, of all things this community had to offer and discuss, I really only ever cared about Casio Prizm discussions. After I moved on from Casio Prizm development – and at a time when forum activity was already decreasing – I tried to foment discussions on my Clouttery project, with mild but disappointing success.

Cemetech is a bit of a strange beast because, at least in my view, it hinges a bit too much on the interests, activities and projects of its founding member KermM and other staff, which to me at least, always seemed to be close friends with each other. For one example, I felt like a lot of attention was given to Casio calculators and especially the Prizm models at a time when KermM was “fed up” with TI for some reason, but once TI started releasing new models, with color screens and other features debuted by the Prizm, Casio calculators were slowly forgotten in that community. I’m sure they didn’t do this on purpose – for many years, until the Prizm was launched and caught the eyes of the staff, the community was much more TI-focused than Casio-focused, and it wasn’t unexpected to see it return a bit to its roots. Perhaps I should rephrase my sentence where I said it hinges too much on the staff’s interests… what I mean is, the staff there used to be a discussion promoter, posting a lot on every thread; since KermM kind of left to pursue his PhD and then to be a founder of a startup, Geopipe, activity levels took a hit – at least, and again, from my point of view.

This is a quite anecdotal example… not only is the community this “strange beast”, it’s also focused on the quite niche topic of graphing calculators – even though it always had so many more topics, it was calculator stuff that brought in the most people and the most posts. As a hacker’s platform, graphing calculators are dying, due to new exam regulations in multiple countries imposing restrictions on their hardware and software, and sometimes doing away with this kind of calculators entirely.

It isn’t surprising that a forum about a dying niche subject would be dying. Cemetech now seems down to about 40 posts per day… wait, that doesn’t seem very low. But if you look at the forum index alone, you’ll see that many sections have not even seen a new post in this month, and the number of topics with active discussion seems much lower to me than it once was. Oh well, maybe it’s just me – this is a subjective blog post, after all.

Yet another community focused on graphing calculators – at least initially. This one is much more recent than most of the communities around this topic, but it too has been struggling with lack of activity. In my opinion, it never had that much activity to begin with, but there’s no doubt it went through some rough months – fortunately, it seems to be speeding up a bit now.

CodeWalrus was founded in October 2014… and I’m not sure how to explain this, and I’ll probably get it wrong, but it was founded by people previously associated with Omnimaga (yet another calculator community) – including its founder – but who no longer wanted to be involved in Omnimaga. This older community is, too, pretty much inactive these days (see stats). As for CodeWalrus, which also has a stats page, things look way brighter. At least, you certainly can not accuse the members of not trying to cheer things up.

Before I move on to talking about another forum, note how I said that CodeWalrus was initially more focused on graphing calculators (by virtue of the interests of the members, not because that was the topic imposed by the administration). Well, their strategy – from the very first day – for catering to people with other interests seems to have paid off. A brief look at the active topic lists shows no posts related to graphing calculators… wow.

I don’t think this community needs to be introduced to my readers. It’s a giant community and I can’t quite take its pulse, unlike what I did with the other anecdotes in this post. With over eight million members, its scale is completely different from the other forums I mentioned so far. It isn’t a dying forum, and that’s why I brought it here: to show that definitely not all forums are dying. Or maybe only big forums survive? We shall look into that in future posts.

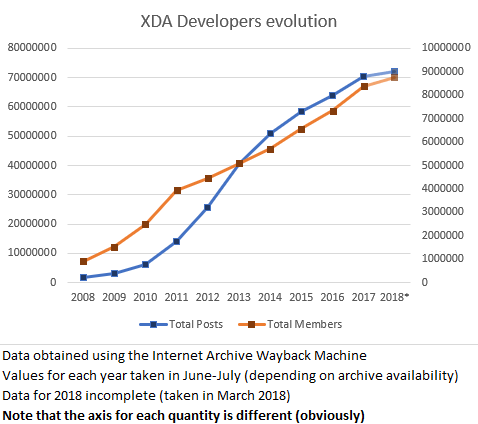

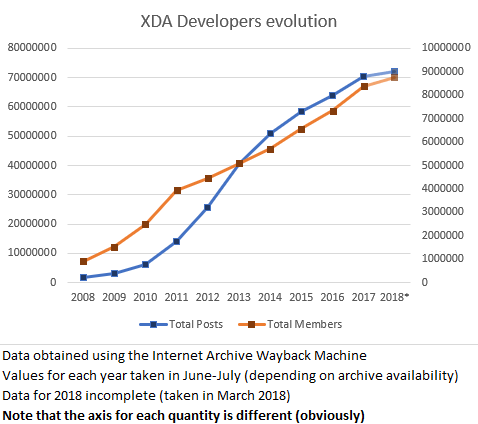

This forum might not be dying, but it could still be interesting to see whether the variation in number of posts and sign-ups is positive or negative. I searched, and searched, and could not find a live statistics page, or any up-to-date report. With a forum so big, it’s quite possible that computing these kinds of statistics in a real-time fashion is simply unfeasible. However, certain forum views still show the current totals at the bottom. With the help of Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, we can plot stuff over time…

Take from that what you will… but its growth doesn’t seem to be decelerating, even if it apparently isn’t as active as it was in 2012-2013. It could also have happened that despite the slight decrease in the speed at which new posts are added, the quality of the discussion has improved, with an overall better result.

Still on the big forums league, SkyscraperCity – a community with about one million members and over 100 million posts that claims to be the world’s biggest community on “skyscrapers and everything in between”, founded in 2002. In practice, it’s a forum about urbanism that, along many international discussions, also hosts some regional sub-forums where all kinds of stuff is discussed. For example, in the Portuguese forum, you can find topics ranging from architecture and urbanism to transportation and infrastructures, and also general topics about what’s going on in the country as well as completely off-topic stuff like discussion about what’s on TV. It is at SkyscraperCity that you can find the most forum-based discussion around the Lisbon subway, for example – with over 3000 posts per year about that subject alone.

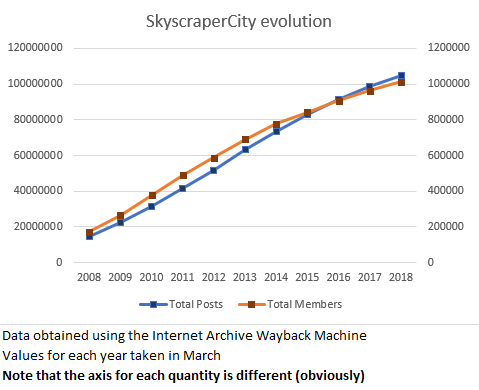

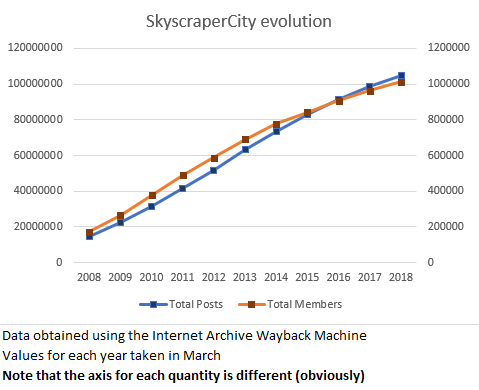

I only participate, precisely, in the Lisbon subway discussions at that forum, so even though I vaguely know about the other sub-forums and topics, I have no idea if the forum is more or less active than it used to be. Using, again, the Wayback Machine, let’s take a look at the evolution in the number of members and total posts in the last 10 years.

This graph is even less interesting than the XDA one. The number of members and posts has been growing essentially linearly. There is a slight deceleration in the last three to four years, especially in the member count, but that could be due to better spammer detection systems (something as simple as a better captcha system could have that effect).

SkyscraperCity is yet another forum that, despite using antiquated software and not having the best availability or reliability history, doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. It isn’t displaying “exponential user growth” like investors and shareholders like so much to hear. But hey, one of the nice things about forums, is that generally they don’t need to boost user counts like that, because they don’t typically have shareholders to report nice numbers to.

Looks like we’re back to the subject of web hosting. LowEndTalk is the discussion forum of LowEndBox, a website that lists deals on low-spec virtual and dedicated private servers. I never participated or followed this forum in any way, but I have known about its existence and have had a good idea of its “dimension” for almost as long as I have known about FreeVPS.

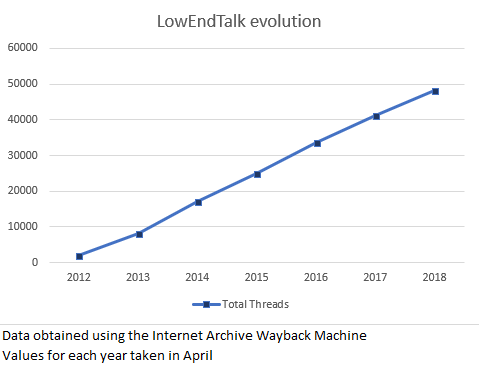

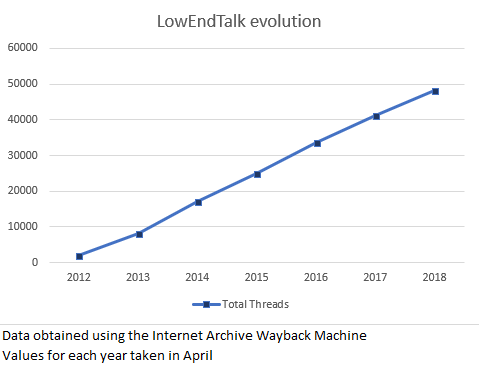

LowEndTalk makes my job a bit hard because, as far as I can see, they don’t list the total number of members nor the total number of posts anywhere. Fortunately, they do show the total number of threads (or “discussions”, as their forum software calls them), rounded to the nearest hundred. Let’s see if we can get any sort of trend out of this. Wayback Machine to the rescue…

Judging by the thread counts alone, looks like LowEndTalk is yet another forum that isn’t going anywhere, with over 7000 new threads being added each year. The chart gives the impression that growth is slightly more linear than it actually is: the rise in the number of threads is actually slowing down a bit, from an average of about 8700 threads/year in 2013-2015 to about 7500 threads/year from 2015 to the present. Nothing to worry about.

You might be wondering why I brought LowEndTalk here, since it’s not an especially big or especially well-known forum, and it’s not a forum I frequent, either. The reason is that during my “research” for this post, a few things caught my eyes when looking at LowEndTalk.

For a start, their forum software (Vanilla Forums) is not one I commonly see in the wild, or at least one that I recognize – despite the fact that according to Vanilla Forums, they are “Used by many of the world’s leading brands”. At least in its LowEndTalk incarnation, it is extremely “clean”, simple and still good looking. It’s not “responsive” web design, but it’s very readable and fast. It’s definitely different from your run-of-the-mill SMF/phpBB/MyBB-powered forum. But is it better? We shall look into this in a future post.

LowEndTalk only became a “traditional forum” in 2011. Before, they were a Q&A website (like StackOverflow, for example) powered by OSQA. Using the Wayback Machine, it’s easy to see that some of the hot topcis were discussions about moving from OSQA to something more appropriate to their needs. Therefore, this community has yet another interesting quirk: they were not born as a “traditional forum”, they actually moved into one after the community was already bootstrapped and a Q&A model was deemed inappropriate.

LowEndTalk have recently set up a Discord “server”. Unlike what seemed to be the plan at CodeWalrus at one point, it is apparently not their intention to move discussion out of the forum and into Discord. Still, I think this is an interesting point for a future post about forum alternatives – what are people moving to, after all?

Including this one here is pretty ridiculous, but I thought I’d do so anyway, even if only as some sort of honorable mention to the thousands of small forums hosting communities of developers and users of open source projects. I feel that these kinds of forums, along with self-hosted issue trackers (such as Flyspray or Trac) were a much more common sighting in the distant past before GitHub.

Anyway, what is Rockbox and their forums? Rockbox is an open-source firmware for that ancient thing smartphones made us forget about, the MP3 player. You know, of the old-school iPod-with-clickwheel kind.

I used Rockbox for a couple years on the 2nd iPod Nano my parents won in some sort of raffle and which they never really heavily used. iTunes made it a PITA to use it; my family (unlike me) isn’t that much into listening to music and maintaining a music library; and finally, my dad was into PDAs and Pocket PCs way before the iPhone even launched.

For us, the thought of playing music on a MP3 player was already kind of strange even when that iPod was brand new – why go through the hassle of using iTunes, transcoding music files, having to charge and carry around yet another device… when we could just take a full-size SD card, insert it into one of these ginormous Pocket PCs (which also made phone calls) and listen to our existing MP3s and WMAs (no M4A transcoding required!) using Windows-freaking-Media Player on Windows Mobile (or any other player of our liking, since those phones could run arbitrary EXEs compiled for Windows Mobile, and many player application alternatives existed).

Anyway, to finish telling yet another personal story of my life: I found out about Rockbox at a point when the iPod was already forgotten in a drawer. Long story short, that iPod got 500% more use ever since I installed Rockbox on it. Rockbox can even run Doom and has a Gameboy/Gameboy Color emulator, how awesome is that? (And no, Rockbox is not Linux-powered, but there was a separate project which ported Linux to some older iPods.) Sadly the capacitors on my iPod’s screen have failed and only 30% of the screen is readable now, making it a bit hard to use the device.

I would still use that iPod to this day if it weren’t for that malfunction (which I don’t feel like spending $10 on a new screen to fix): the iPod has just 4 GB of storage, but Rockbox can play Opus, the awesome audio format that’s simply the best in terms of quality/filesize ratio (and I hope this sentence will look extremely dated in 10 years). I can fit the relevant part of my music library in there by converting over 10 GB of high-quality MP3, M4A and FLAC into less than 4 GB of Opus at 96 kbit/s – which sounds great.

Rockbox, as you might guess, is pretty much dead these days. It never got to the point where it supported the most recent MP3 players or the latest iPod models, thanks to Apple and their locked bootloaders. MP3 players became a niche/audiophile product as people moved on to smartphones and the demand for them dropped; the prices went up as a result. Perhaps most importantly, if it weren’t for the fact that it could support more devices, Rockbox is a finished product: it can play any relevant music format (including tracker music), it has everything you could possibly want from a music player in terms of sound effects/adjustments, playlist control and library browsing. And now for something that might take you off-balance: Rockbox is a project by Haxx – yes, the same Haxx of the extremely popular and successful program curl! In fact, there is a noticeable overlap between both development teams. Both are awesome pieces of software.

I just realized this post was supposed to be about “forums” and not “alternative firmware for embedded devices and opinions about sound formats”… shit. Anyway, Rockbox is dead and, surprise! the forums are pretty much dead too, for obvious reasons – it would be quite interesting if the forums outlived the open source project they were built around, but it doesn’t seem like this will be the case, and I never saw it happen.

Conclusions

Maybe forums aren’t dying left and right like I thought they were. But they don’t seem to be growing as fast as the rest of the internet. IDK, at this point I’m just making stuff up because I don’t know how fast “the internet” grows. Perhaps it has to do with that shareholder thing, forums don’t usually have to report inflated numbers to anyone. Or maybe people are really locked down inside the bubble-decorated walled-garden of the EVIL ZUCC. Yeah, let’s pretend that is the case, so that my plans for the following posts are not completely foiled. As for this pointless anecdote-based post, its end is here.

BTW: did you know I started working on this post on the 7th of March… only to leave it rotting unfinished since the 9th of March… and finally finish it today? But it’s fine: this way, I could include a ZUCC reference while people are still outraged at Facebook, and before they go back to using it again happily ever after.

October 10, 2017 / gbl08ma / 2 Comments

A few years ago, I was very active in the Casio Prizm development community, having developed three notable add-ins, contributed to the Prizm wiki, libfxcg (my fork), and even done a bit of reverse-engineering (the calculator OS is closed-source and there is no official SDK), that resulted in the discovery of a couple of syscalls and more detailed documentation on some other ones. Because of this, once in a while I still get messages about my add-ins, which I’m happy to support when possible. Most annoyingly, I also get messages about Prizm development, usually about how to start making add-ins.

Why are these messages annoying? Because I don’t really know how to answer. When I started developing add-ins for the Prizm, I had little to no knowledge of the C programming language, and yet, despite the fact that add-ins can’t make use of all the stuff “normal” C programs can (the libc provided by libfxcg is incomplete; the filesystem uses a different API, there’s no threading, the stack is giant compared to the heap, etc.), I managed to learn it. It certainly helped that I had some previous experience with programming in other languages, even if it was just sloppy code, but I don’t have much of an idea of what to say to someone who intends to learn programming using the Prizm.

I usually end up saying that learning programming using the Prizm it’s a bad idea, probably coming across as extremely discouraging. However, I do hope it’s for the best, and that these people will still learn programming – just not by developing add-ins! Had my first contact with programming been through Prizm add-in development, most certainly I would have chosen other career path than computer engineering. I mean this seriously. I’m glad my first contact with programming was through sloppy Visual Basic code. Anyway, I already wrote a post on my programming experience – it needs updating, but it should do.

Learning how to program, even in a “easy” language and common platform, can be overwhelming; for a programmer that is used to higher-level programming, learning the Prizm, a poorly documented platform with a small developer community, can be overwhelming; combine learning how to program with learning a poorly documented embedded system, and it will most likely be very overwhelming. Of course, nothing will stop someone extremely motivated – hopefully, not even my less encouraging replies, or this blog post.

What follows is the partial reproduction of an email I recently sent, in reply to yet another of these inquiries on how to start developing for the Prizm. I have edited it to make it less specific to the situation of the person I was replying to. I’ll also use the terms “Prizm” and “fx-CG 50” interchangeably, as add-ins built for the former run, with a few exceptions due to sloppy coding (one of mine’s one of these exceptions…), on all Casio Prizm models: fx-CG 10, fx-CG 20 and fx-CG 50.

Do you have any previous programming experience? If not, I honestly do not recommend starting with the Prizm or any other Casio graphical calculator. If yes, then be aware that this is not an “easy” platform to develop for. Either way, here are a few reasons why:

- Prizm add-ins are written in C or very limited C++ (that might as well be considered C). By today’s standards, these are very low-level languages that require manual memory management and a very good awareness of the machine. They also provide very little protection from programmer mistakes. While some people had C as their first programming language, it is by no means a beginner-friendly language.

- Even if you already know C well, or if you learn it from any common book, tutorial or course, you’ll be disappointed to find out that much of the standard library is not present, or is insufficiently implemented, in the Prizm calculators.

- Add-in development for the Prizm was made possible through reverse-engineering and educated guesses based on what was known about previous models like the fx-9860G. While we now understand the essential things about the OS on these calculators, many things are yet to be known.

- Documentation is lacking and the community is not very large. This essentially means that you won’t be able to just google your way through many problems.

- Reverse-engineering/documentation and development efforts for the Prizm have basically stalled. You’ll also find many materials that mention the fx-CG 10/20, but since the fx-CG 50 is basically just a faster version of these with a mostly compatible OS (although some things like memory addresses have changed), almost everything you’ll ever need will still apply.

Now, I’m sorry if I came across as dismissive or as discouraging, I’m just trying to make sure you know what’s in front of you.

For Casio Prizm development specifically, this is where I can point you:

Prizm forums at Cemetech

Use these to ask any questions you might have and try to find solutions to any problems you encounter. There are also some guides there, mainly on how to set up the development environment (compiler and such), but I’m afraid they might be a bit out of date. However, as I said, development efforts have mostly stalled, so consider anything from 2014 or early 2015 as up-to-date. Specifically, do not follow the “[HOWTO] Prizm C Development” in there, as it is out of date.

Prizm wiki

This wiki contains much information on the calculator, the reverse-engineered OS functions (“syscalls”) that can be used from add-ins, etc. It also contains more up-to-date instructions on how to set up a development environment.

Personally, I have mostly moved on from Prizm development about three years ago, as I began pursuing a degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering. Every year or so, I make a short comeback to fix urgent issues with my add-ins and eventually make them compatible with new OS versions and calculator models, as is the case of the fx-CG 50, as long as that does not require too much time/effort. As time passes and I work with other technologies, the more I realize more how “hard” of a platform the Prizm is, and the less motivated I am to build stuff for it again; the fact that I no longer use my fx-CG 20 nearly as much since high school, also doesn’t help.

I’m afraid I can’t help you much more, as I’ve forgotten much of what I knew about the Prizm, both the “theoretical” and “practical” knowledge, and I no longer have practical access to a development environment for it. I tried to put as much of my knowledge as I could into the Prizm wiki before I left, and I believe that the people that now frequent the Cemetech forums will be able to help you much better than I can.

I think that one day I might find some interesting in working on the Prizm again, but perhaps more from a reverse-engineering angle. As for the fun in developing for a constrained, embedded system, there are much more appealing constrained systems out there, like the ESP8266.

August 23, 2015 / gbl08ma / 1 Comment

Go to the bottom, “Summing it up”, for the TL;DR.

The day I turn this website into a portfolio/CV-like thing will come sooner or later, and arguably that’s a better use for the domain gbl08ma.com than this blog with posts nobody cares about – except when I rant about new operating systems from Microsoft. But if you really care about such posts, do not worry: the blog will still exist, it just won’t be as prominent.

Meanwhile, and off-topic intro aside, the content usually seen on such presentation websites everyone-and-their-cat seems to have these days, will have to wait. In anticipation for that kind of stuff, let’s go in a kind of depressing journey through my eight years programming experience.

The start

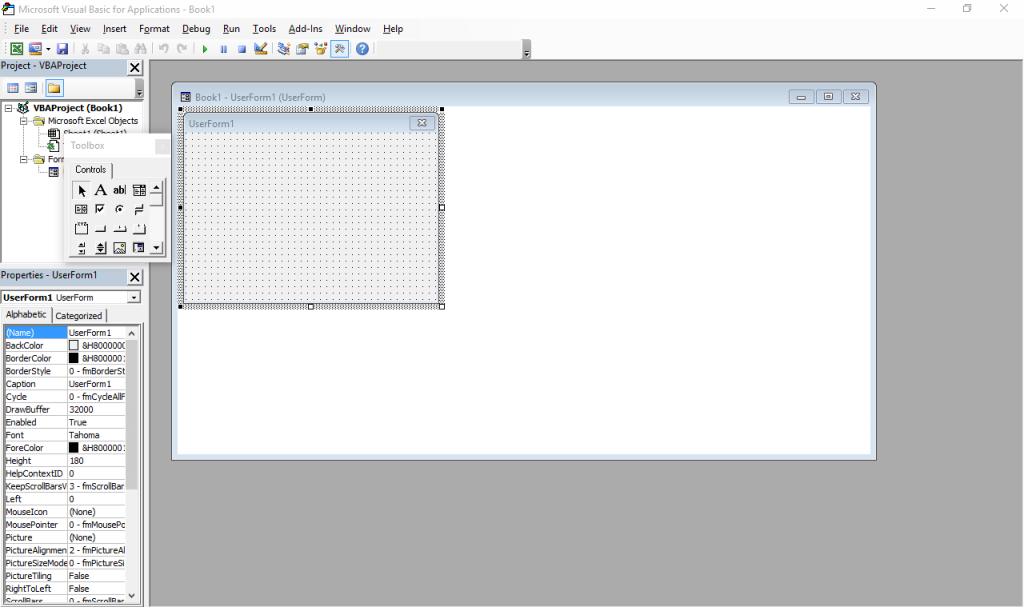

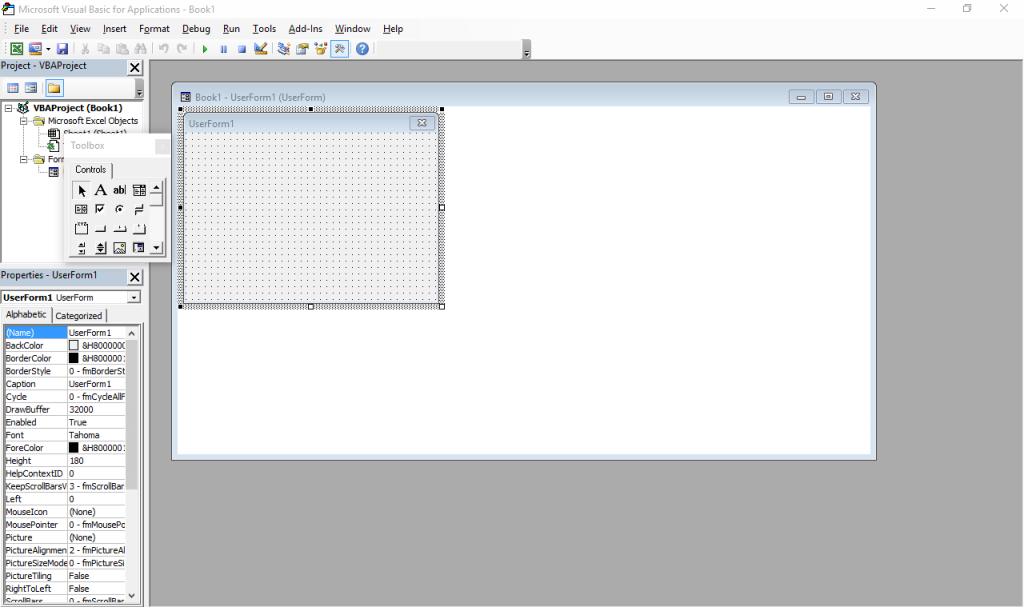

The beginning was what many people would consider a horror movie: programming in Visual Basic for Applications in Excel spreadsheets, or VBA for short. This is (or was, at the time; I have no idea how it is now) more or less a stripped down version of VB 6 that runs inside Microsoft Office and does not produce stand-alone executables. Everything lives inside Office documents.

It still exists – just press Alt+F11 in any Office window. Also, the designer has Windows 7 Basic window styles… on Windows 10, which supposedly ditched all that?

I was introduced to it by my father, who knows his way around Excel pretty well (much better than I will probably ever will, especially as I have little interest). My temporal memory is quite fuzzy and I don’t have file timestamps with me for checking, so I was either 9, 10 or 11 years old at the time, but I’m more inclined to think 9-10. I actually went quite far with it, developing a Excel-backed POS system with support for costumer- and operator-facing character LCD screens and, if I remember correctly, support for discounts and loyalty cards (or at least the beginnings of it).

Some of my favorite things I did with VBA, consisted in making it do things it was not really designed for, such as messing with random ActiveX controls and making it draw strange-looking windows (forms) and controls through convoluted Win32 API calls I’d have copied from some website. I did not have administrator rights to my computer at the time, so I couldn’t just install something better. And I doubt my Pentium III-powered computer, already ancient at the time (but which still works today), would keep up with a better IDE.

I shall try to read these backup CDs and DVDs one day, for a big trip down the memory lane.

Programming newb v2

When I was 11 or 12 I was given a new computer. Dual core Intel woo! This and 2GB RAM meant I could finally run virtual machines and so I was put on probation: I administered the virtual computers, and soon the real hardware followed (the fact that people were tired of answering Vista’s UAC prompts also helped, I think). My first encounter with Linux (and a bunch other more obscure OS I tried for fun) was around this time. (But it would take some years for me to stop using Windows primarily.)

Around this time, Microsoft released the Express (free) editions of VS 2008. I finally “upgraded” to VB.NET, woo! So many new things to learn! Much of my VBA code needed changes. VB.Net really is a better VB, and thank Microsoft for that, otherwise the VB trauma would be much worse and I would not be the programmer I am today. I learned much about the .NET framework and Visual Studio with VB.NET, knowledge that would be useful years later, as my more skilled self did more serious stuff in C#.

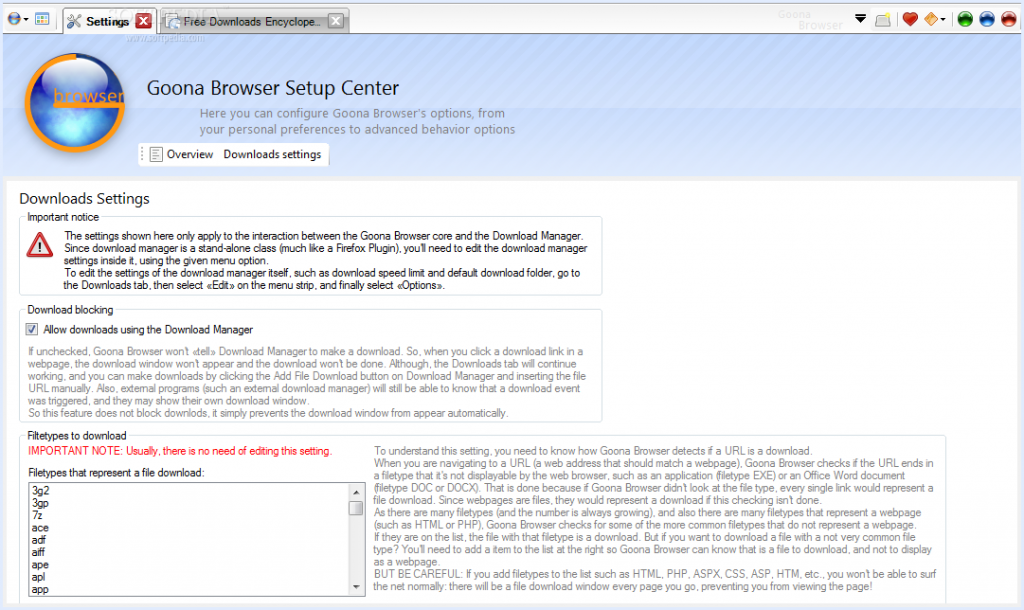

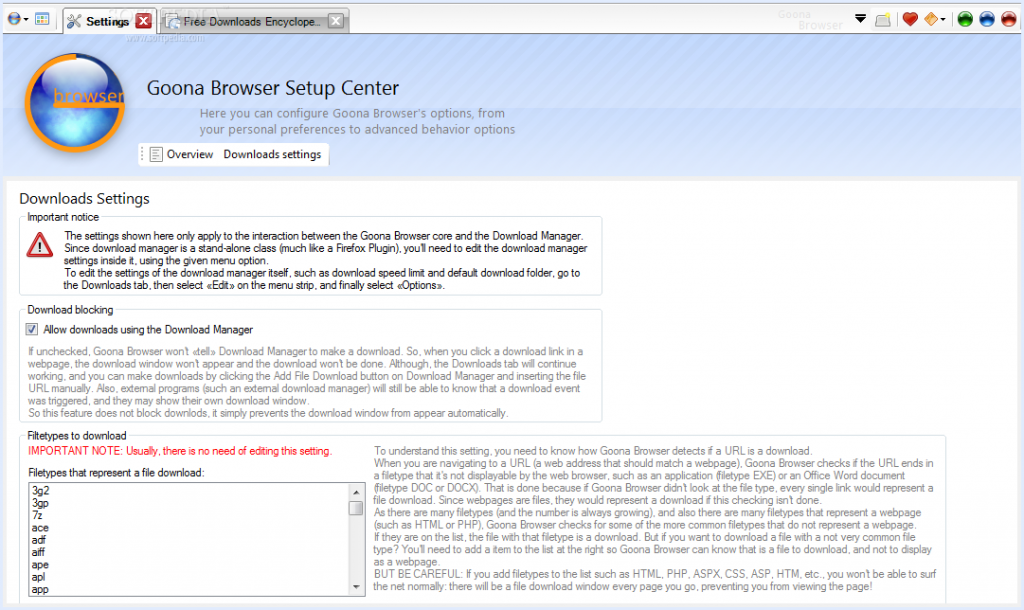

In VB.NET, I wrote many lines of mostly shoddy code. Much of that never saw the light of day, but there are some exceptions: multiple versions of Goona Browser made their way to the public. This was a dual-engine web browser with advanced UI, and futuristic concepts some major players copied, years later.

How things looked like, in good days (i.e. when it didn’t crash). Note the giant walls of broken English. I felt like “explain ALL the things”! And in case you noticed the watermark: yes, it was actually published to Softpedia.

If you search for it now, you can still find it, along with its website which I made mostly from scratch. All of this accompanied by my hilariously broken English, making the trip to the past worth its weight in laughs. Obviously I do not recommend installing the extremely buggy software, which, I found out recently, crashes on every launch but the first one.

Towards the later part of my VB.NET era, I also played a bit with C#. I had convinced myself I wanted to write an operating system, and at the time there was a project called COSMOS that allowed for writing (pretty limited) OS with C#… of course my “operating” systems were not much beyond a fancy command line prompt and help command. All of that is, too, stored in optical media, somewhere… and perhaps in the disk of said dual-core computer. I also studied and modified open source programs made in C# (such as the file downloader described in the Goona Browser screenshot) for my own amusement.

All this happened while I developed some static websites using Visual Web Developer Express as editor. You definitely don’t want to see those (mostly never published) websites, but they were detrimental to learning a fair bit of HTML and CSS. Before Web Developer I had also experimented with Dreamweaver 8 (yes, it was already old back then) and tried my hand at animation with Flash 8 (actually I had much more fun using it to disassemble existing SWFs).

Penguin programmer

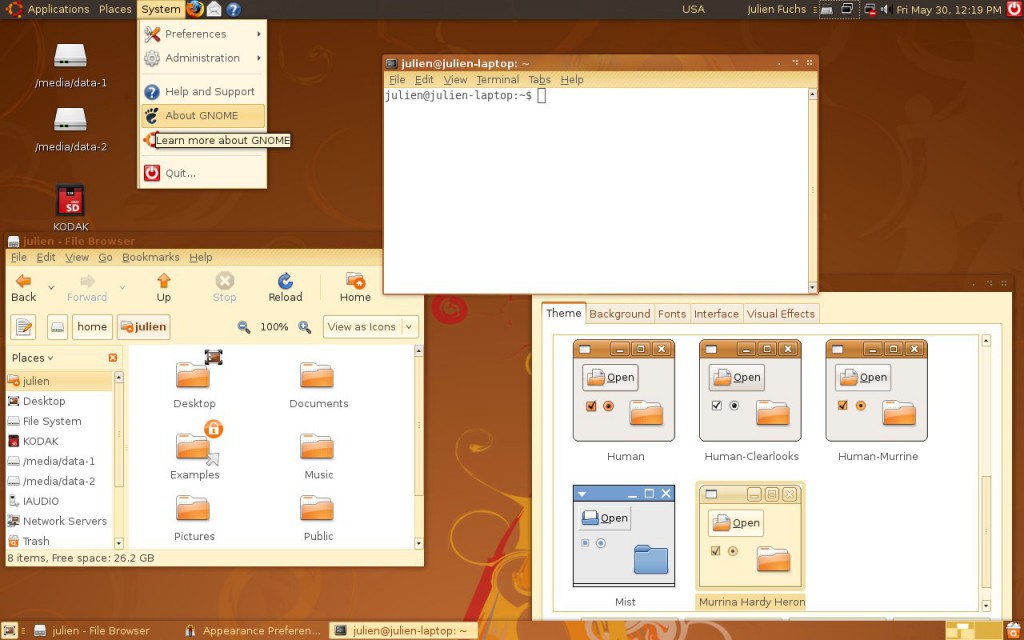

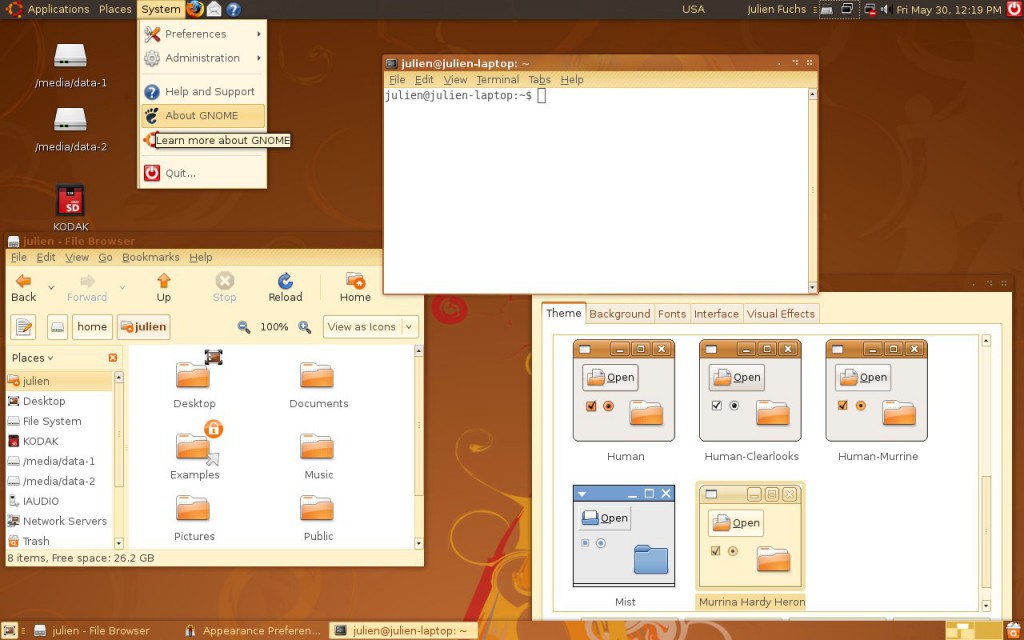

At this point I was 13 or so, had my first contact with Linux more than done, through VMs and Live CDs, aaand it happened: Ubuntu became my main OS. Microsoft “jail” no more (if only I knew what a real jailed platform was at the time…). No more clunky .NET! I was fed up with the high RAM usage of Goona Browser, and bugs I was having a hard time debugging, due to the general code clumsiness.

How Ubuntu looked like when I first tried it. Good times. Canonical, what did you do?

For a couple of years, in terms of desktop development, I only made some Python scripts for my own amusement and played a very small bit with MonoDevelop every time I missed .NET. I also made a couple Lua scripts for Rockbox. I learned much about Linux usage and system maintenance as I used it more and more on my own computers and on my first Virtual Private Servers, which I got after much drama in the free web hosting communities. Ugh, how I hate CPanel.

It was around this time that g.ro.lt and n.irc.su appeared. g.ro.lt was a URL shortener that would later evolve into 4.l.to and later tny.im. n.irc.su was a social network built on Elgg, which obviously failed. I also made some smaller websites, like one that would take you to random image hosting websites, URL shorteners and pastebins, so you would not use the same service every time you urgently needed one. These represented my first experiences with PHP programming.

I have no pictures to show. The websites are long gone, not on the Internet Archive, and if I took screenshots, I have no idea where I put them. Ditto for the logos. I believe I still have the source code for the random-web-service website somewhere, at least the front page layout.

All this working on top of free stuff: free (and crappy) subdomains, free (and crappy) web hosting, free (and less crappy) virtual servers. It would take me some time until I finally convinced myself I needed to spend some money for better reliability, a gist of support and less community drama. And even then I would spend Bitcoin, which I earned back when it was really cheap, making the rounds of silly faucets and pulling money out of CPAlead-like offers through the use of multiple proxies (oh, the joy of having multiple VPS…). To this day I still don’t have a PayPal account.

This time, and when I actively developed tny.im (as opposed to just helping maintain it), was the peak of my gbl08ma-as-web-developer phase. As I entered and went through high school, I would get more and more away from HTML and friends (but not server maintenance), to embrace something completely different…

Low level, little resources: embedded systems

For high school math everyone had to use a graphing calculator. My math teacher recommended (out of any interest) Casio calculators because of their ease of use (and even excitedly mentioned, Casio leaflet in hand, the existence of a new and awesome color screen model that “did everything and some more”). And some days later I had said model in my hands, a Casio fx-CG 20, or Prizm, which had been released about a year before. The price difference from the earlier dot-matrix screen Casio calcs was too small to let the color screen go.

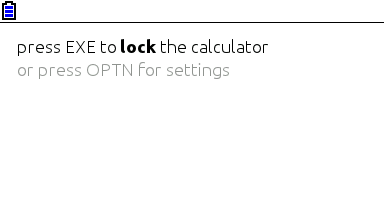

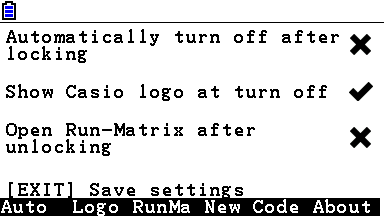

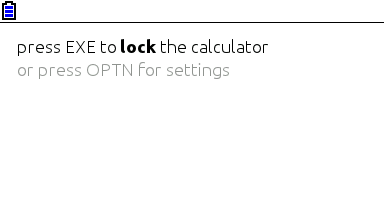

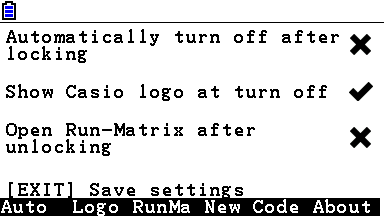

I was turning 15, or had just turned 15. I remember setting up the calculator and thinking, not much after, “I want to code for this thing”. Casio’s built-in Basic dialect is way too limited (and after having coded in “real” languages, Basic was silly). This was in September 2011; in March next year I would be releasing my first Prizm add-in, CGlock, a calculator PIN-locking software.

Minimalist look, yay! So much you don’t even notice it’s a color screen.

This was my first experience with C; I remember struggling with pointers, and getting lots of compilation warnings and errors, and run-time errors. Then at some point everything just “clicked in” and C soon became my main language. Alas, for developing native software for the Prizm, this is the only option (besides using C++ without most of its features, not even the “new” keyword).

The Prizm is a horrible platform, especially for newbie C programmers. You can’t use a debugger, nor look at memory contents, the OS malloc/free implementation has bugs (and the heap is incredibly small, compared to the stack) and there’s always that small chance some program damages your calculator, or at least corrupts your estimated files and notes. To this day, using valgrind and gdb on the desktop feels to me as science fiction made true. The use of alloca (stack allocation) ends up being preferred in relation to dynamic allocation, leading to awkward design decisions.

Example of all the information you can get about an error in a Prizm add-in. It’s up to you to go through your binary (and in some cases, disassemble the OS) to find out what these mean. Oh, the bug only manifests itself when compiling with optimizations and without symbols? Good luck…

There is a proprietary emulator, but it wasn’t designed for software development and can’t emulate certain things. At least it’s better than risking damage to expensive hardware. The SuperH-4 CPU runs at 58 MHz and add-ins have access to about 600 KiB of memory, which is definitely better than with classic z80-powered Texas Instruments calculators, but one still can’t afford memory- or CPU-intensive stuff. But what you gain in performance and screen resolution, you lose in control over the hardware and the OS, which still have lots of unknowns.

Programming for the Prizm taught me how it’s like to work without the help of the C standard libraries (or better, with the help of incomplete and buggy standard libraries), what a stack overflow looks like (when there’s no stack protection), how flash memories work, what DMA is, what MMUs do and how systems can be bricked when their only bootloader is not read-only. It taught me how compilers work from an end-user perspective, what kind of problems and advantages optimizations introduce, and what it’s like to develop parts of the C standard library.

It also taught me Casio support in Portugal (Ename) is pretty incompetent at fixing calculators, turning my CG 20 into a CG 10 and leaving two big capacitors out of a replacement main board. In this hardware topic, I learned quite a bit about digital logic from Prizm hardware discussions at Cemetech. And I had some contact with SH4 assembly and a glimpse into how to use IDA Pro. Thank you Casio for developing a system that works so well and yet is so broken in so many under-the-hood ways, and thank you Cemetech for briefly holding the Prizm higher than TI calcs.

I developed other add-ins, some from scratch and others as ports of existing PC software (such as Eigenmath). I still develop for the Prizm from time to time, but I have less and less motivation as the homebrew community has stagnated and I use my Prizm much less, as I went to university. Experience in obscure calculator platforms does not make for a nice CV.

Yes, in three years or so I went from the likes of Visual Studio to a platform where the only way to debug is to write text to the screen. I still like embedded and real-time programming a lot and have moved to programming more generic and well-known things such as the ESP8266.

Getting in the elevator

During the later part of high school (which I started in the fall of 2011 and ended in the summer of 2014), I did more serious Python stuff, namely Mersit, later deprecated in favor of Picored, which is not written in Python but in Go. Yes, I began trying higher-level stuff again (higher level, getting in the elevator… sorry, I’m bad at jokes).

My first contact with Go was when I was 17, because I wanted to develop something that ran without external dependencies (i.e., unlike Java or .NET) and compiled to native code. I wanted to avoid C/C++, but I wasn’t looking for “a better C” either, so Rust was not it. Seeing so much stuff about Go at Hacker News, one day I decided to try my hand at it and I like it quite a lot – I’m still unsure if I like it because of the language itself or because of the great libraries one can use with it, but I think both play an important role.

This summer I decided to give C# another chance and I’m quite impressed – turns out I like it much more than I thought. It may have something to do with trying it after learning proper languages vs. trying it when one only knows VB. I guess my VB.NET scars are healed. I also tried a bit of Java, in my first contact with it ever, and it seems my .NET hate converted into Android API hate.

Programming with grades

University gave the opportunity (or better, the obligation) of having other people criticize my code. The general public could already see the open-source C code of my Casio Prizm add-ins, and even the ugly code of Goona Browser, but this time my code was getting graded. It went better than I initially thought – I guess the years of experience programming in different languages helped, especially as many of the people I’m being compared with have only started programming this year.

In the first semester we took an introductory programming course, which used Python, and while it was quite easy for me, I took the opportunity to learn Python to a greater depth than “language in which to write quick and dirty glue code”. You see, until then I had not used classes in my Python code, for example. (This only goes to show Python is a versatile language, even if slow.)

We also took an introductory computer architecture course where we learned how basic CPUs work (it was good for gluing all the separate knowledge I already had about it) and programmed in assembly for a course-specifc CISC-like architecture. My previous experience with reading SH4 assembly proved quite useful (and it seems that nowadays the line between RISC and CISC is more blurred than ever).

In the second semester, I had the opportunity to exercise my C knowledge, this time not limited to the Prizm platform. More interestingly, logic programming, a paradigm I had no intention of ever programming in, was presented to us. So Prolog it was. It went much better than I anticipated, but as most other people who (are forced to) learn it, I have no real use for it. So the knowledge is there, waiting for The Right Problems(tm). I am afraid I’ll forget much of it before it becomes useful, but if there’s something picking C# up again taught me, is that I can pick up pretty fast skills learned and abandoned long ago.

The second year is about to begin and there’s some object-oriented programming coming, I hope I do well.

Summing it up

I have written non-trivial amounts of code in at least 8 languages: Visual Basic, PHP, C#, Python, Lua, C, Go, Java and Prolog. I have contacted with two assembly dialects and designed web pages with HTML, CSS and Javascript, and of course automated some tasks with bash or plain shell scripting. As can be seen, I’m yet to do any kind of functional programming.

I do not like “years of experience” as a way to measure language proficiency, especially when such languages are learned for use in short-lived side projects, so here’s a list with an approximate number of lines of code I have written in each language.

- C: anywhere between 40K lines and 50K lines. Call it three years experience if you will. Most of these were for Prizm add-ins, and have since been rewritten or heavily optimized. This is changing as I develop less and less for the Prizm.

- PHP: over 15K lines, two years if you want to think that way. The biggest chunk of these were for developing the additions to YOURLS used in tny.im, but every other small project takes its own 200-500 lines of code. Unfortunately, most of this is “bad” code, far from idiomatic. The usual PHP mess, you know.

- Python: at least 5K lines over what amounts to about six months. Of these, most of the “clean” lines (25-35%) were for university projects.

- Go: around 7K lines, six months. Not exactly idiomatic code, but it’s clean and works well.

- VBA: uh, perhaps 3 or 4K lines, all bad code 🙂

- VB.NET: 10K lines or so, most of it shoddy code with lots of Try…Catch to “fix” the problems. Call it two years experience.

- C#: 10K lines of mostly clean and documented code. One month or so 🙂

- Lua: mostly small glue scripts for my own amusement, plus some more lines for use in games such as Minetest, I estimate 3-4 K lines of varying quality.

- Java: I just started, and mostly ported C# code… uh, one week and 1.5K lines?

- HTML, CSS and JS: my experience with JS doesn’t go much beyond what’s needed to modify DOM elements and make simple AJAX requests. I’ve made the frontend for over 5 websites, using the Bootstrap and INK frameworks.

- Prolog: a single university assignment, ~250 lines or one month. A++ impression, would repeat – I just don’t see what for.

In addition to all this, I have some experience launching the programs and services I make – designing logos/branding, versioning, keeping changelogs, update instructions, publishing, advertising, user support. Note that I didn’t say I’m good at any of these things, only that I have experience doing them, for better or worse…

Things I’d like to have more experience with:

- Continuous integration / testing in general;

- Debugging code outside of .NET/Visual Studio and printing debug lines in C;

- Using Git and other VCS in big repos/repos with more people (I want to see those merge conflicts and commits to the wrong branch coming);

- Server-side web development on something other than PHP and Go. And learning to use MVC frameworks, independently of the language;

- C++ (and Java, out of necessity. Damned Android);

- Game development. Actually, this is how many people start, but I’m so cool that I started by developing POS software 🙂

March 9, 2015 / gbl08ma / 0 Comments

Here’s a new video showing another set of features of the upcoming v1.5 of my Utilities add-in, for the Casio Prizm. Note that this is only an early preview and some things may change until the final release. Meanwhile, feel free to comment.

February 2, 2015 / gbl08ma / 0 Comments

Just two days ago, I mentioned in this blog the Windows port Microsoft made for the ARM architecture:

Microsoft, for things like the (abandoned) Windows RT and Windows Phone, besides porting some of the upper layers of the Windows stack and developing new ones, also had to do additional work to get the NT kernel to run on such hardware. It’s worth mentioning that despite that effort, Windows Phone 8+ has hardware requirements higher than those of Android (comparing versions released in the same time span, please correct me if I’m wrong).

Today, as I open the web browser I’m greeted by multiple related news: a quad-core ARMv7 / 1 GB RAM version of the popular Raspberry Pi board, named “Raspberry Pi 2”, was released, will run Ubuntu Snappy Core, and, mind you, Windows 10.

Now that Windows RT is pretty much dead in the water, it looks like Microsoft found at least one use for their port besides Windows Phone: a strategically introduced “Windows 10 for makers”, which is free – something that would come out as impossible some years ago, in the license-angry Microsoft phase. (Yes, just like they also offered the Windows 8.1 license to OEMs of tablets with screen >= 7 inches, and apparently will offer Windows 10 to Windows 7 and 8.1 users for one year after its release). Of course, there’s no news of this Windows version being the slightest open-source – that is something that in the beginning of 2015, is still thought as “impossible” – but Microsoft is making promising steps, after having open-sourced the .NET framework.

Now, let me explain: while this is a nice move from Microsoft, is not something that leaves me particularly happy (in fact, it leaves me somewhat worried, and it’s not because “OMG OMG Linux is going to lose market share”). For starters, there’s the fact that there have been way more powerful ARMv7 devices around for a long time, for a similar or equal price ($35 USD) – take a look, for example, at the ODROID-C1, so why didn’t Microsoft decide to offer Windows for those too?

The answer, in my opinion, is very simple: Microsoft wants to “look cool”, and benefit from the free advertising and consequent increase of popularity a partnership with the Raspberry Pi Foundation has. Releasing Windows 10 for ARM in a more flexible setup (one that would support different boards besides the new Raspberry Pi) would be even more interesting to the community and probably more flexible for wearable, IoT, etc. projects, but that’s not the path they chose.

Supporting only the Raspberry Pi is also the easiest option, partly due to the lack of standards in the ARM world, which I complained about in the aforementioned blog post. Supporting other boards would lead to a lot of work supporting the different SoC, different peripherals, different boot methods and imaging formats (nothing that Microsoft couldn’t abstract away with a generic second-stage bootloader for WIM files), etc. In other words, it would leave them with as much work as the Linux community has in order to support different embedded systems and CPU architectures (heh).

Something that’s still unclear to me is the licensing part. This Windows version, while free, certainly comes with caveats. I’m sure Microsoft won’t allow using it on consumer products based on the Raspberry Pi (for example, using the upcoming version 2 of the Compute Module), as otherwise it would constitute a free alternative to licensing Windows Embedded. I also expect this version to come severely crippled as not to be able to act as a server; otherwise, expect some cheap Windows servers coming up soon. Even if it’s not crippled, the EULA rules it all, which means that even if a port of this Windows to other ARM boards and devices was possible, or if someone starts selling RPi-based Windows ARM servers, it most likely would not have Microsoft’s blessing.

I’m also a bit worried that the Raspberry Pi Foundation might start to push for Windows instead of Linux, especially since I bet the Windows port will be much more popular than the Linux distros. Doing so would kill half of the purpose of the whole Raspberry Pi thing, in my opinion. Most kids, given the opportunity to use the same user interface and some of the programs they are already used to, will never try to learn new things, much less tinker with them. Having them use a different GUI, or perhaps no GUI at all, by booting directly to a shell (try that, Windows! The closer you can get is the command line on a Windows Recovery Environment! heh) allows for an experience that is, from the start, much different from what they would get with a typical off-the-shelf computer.

By making people move out of their “comfort zone”, the Raspberry Pi Linux distros encouraged people to learn their way around a different system. I’m afraid people who buy a Raspberry Pi and promptly install Windows on it will keep without knowing what a command line is, and will keep doing the same things they did on their full computers. Text-based UIs are definitely not the best option for many/most things, but there are many things they’re better at than GUIs, and more importantly, some people find them out to discover they like them much more than GUIs. But if these people are never given the opportunity, they will never find it out.

Now I must admit, it would be super awesome if Microsoft came up with something like FX!32 but for running x86 binaries on ARM. That would probably require an even more restrictive EULA and/or more crippling for this Raspberry Pi version, as then people would be able to run, for example, all sorts of existing server software that currently requires a paid Windows Server license.

To conclude, I don’t think Microsoft is actually interested in making Windows available for more devices or actually making it a viable choice for low-cost embedded hobby projects and consumer products. They are just trying to gain popularity among not only the general public, but also among the developer and hobbyist community. Unfortunately, I’m not sure if this movement of “embracing OSS and open-sourcing ALL THE THINGS!” is going to last when/if Microsoft reaches their market share goals.

We can look into how the competition did: Android, initially pretty much completely open source, was made more closed as its market share increased. Google keeps on moving more and more things to closed-source blobs under their control, which has upsides (it’s easier to update many parts of the OS) and many downsides (lower user control, etc.). I wonder and worry if Microsoft will do something similar as their popularity endeavors are successful, turning their back on users, developers and all this “freedom hype” once again.

January 31, 2015 / gbl08ma / 0 Comments

On 24th June last year, Version 1.4 of my Utilities add-in for the Casio Prizm calculators was released. The plan was for this to be final release of said software, with any further versions being bug-fixing only, and because of this, it was even more thoroughly tested than previous stable releases.

Ironically enough, an apparently innocent code optimization, introduced at a late development stage, introduced a bug in the Tasks functionality of the add-in, where a reference to a nonexistent memory object may happen when there are no tasks. At this point, I was more or less tired of the Casio Prizm platform, because of the many issues I have described throughout the years, and which the homebrew development community is yet to fully solve. However, as time went by, occasionally I’d look into my Prizm projects and I’d inevitably end up optimizing yet another function, or adding another small functionality.