Musings about Watch Dogs

Before I start, a word about this website. It has mostly sat abandoned, as having a full-time software development job doesn’t leave me with the comparatively endless amounts of free time and mental bandwidth I once had. What remains, in terms of screen time, is usually spent working on other projects or doing things unrelated to software development that require lower amounts (or different kinds) of mental activity, like playing ViDYAgAMeS, arguing with people on Discord, or mindlessly scrolling through a fine selection of subreddits and Hacker News. While I quite enjoy writing, it’s frequently hard to find something to write about, and while I have written more technical posts in the past – this one about MySQL being the most recent example – these often feel too close to my day job. So, for something completely different, here’s some venting about a video game series – this was in the works for over a year, and is my longest post yet. Maybe this time I’ll actually manage to start and finish a series of blog posts.

Introduction

Watch Dogs is an action-adventure video game series developed and published by Ubisoft and it is not their attempt at an Animal Crossing competitor, unlike the name might suggest. The action takes place in open worlds that are renditions of real-life regions; at the time of writing, there are three games in the series: Watch Dogs (WD1), released in 2014 and set in a near-future reimagination of Chicago; Watch Dogs 2 (WD2), a 2016 game set in a similar “present-day, but next year” rendition of the San Francisco Bay Area, and Watch Dogs: Legion (WDL), a 2020 game set in a… uh… Brexit-but-it’s-become-even-worse version of London. The main shtick of these games, in comparison with others in the same genre, is their heavy focus on “hacking,” or perhaps put more adequately, “an oversimplification, for gameplay and storytelling purposes, of the new delicate information security and societal challenges present in our internet-connected world.”

The games fall squarely into two categories: “yet another Ubisoft open world game” and what some people call “GTA Clones.” It’s hard to argue against either categorization, but the second one, in itself, has some problems. The three Watch Dogs games came out after the initial release of the latest entry in the Grand Theft Auto series (GTA V in 2013), and GTA VI is yet to be officially announced, so snarky people like me could even say that, if anything, Watch Dogs is a continuation, not a clone, of GTA!

More seriously, there are people on the internet who will happily spend some time telling you how “GTA clone” is a terrible designation that is actually hurting open world games in general, by discouraging developers from making more open world games with a modern setting – and I generally agree with them. But I prefer to attack this “GTA clone” designation in a different way, the childish one, where you point the finger back the accuser and yell “you too!”: GTA Online has, in multiple of its updates, also “cloned” some of the gameplay elements most recently seen in Watch Dogs, and GTA in general has also taken inspiration from different open world games that were released over the years.

In a 2018 update, Rockstar brought a “Player Scanner” to GTA Online, which is reminiscent of the “Profiler” in Watch Dogs games, and in the same update, they also introduced weaponized drones that can be compared to the drone in WD2. More recently, GTA Online received a new radio station whose tracks are obtained from collectibles spread around the world – similar to how the media player track list can be expanded in WD1. I doubt that Watch Dogs was the primary motivation or inspiration for these mechanics, and they were hardly exclusive to Watch Dogs, but the point is that the “cloning” argument can go both ways.

Nowadays, when it comes to open world games, there’s hardly anyone “cloning” a particular game series. Watch Dogs games are GTA competitors, but the same can be said about countless other games, including many that don’t even make use of open world mechanics. None of this negates the fact that, despite not being a “GTA clone,” Watch Dogs ticks all the boxes of said unfortunately named category, for which a better name would totally be “open world games set in a place recognizable as the world we presently live in.” And therefore I won’t hide the fact that many of the comparisons I’ll make will be directly against the two “HD Universe” GTA titles, IV and V, as these are definitely the most well-known and successful games in said category.

I have played through all three games in the Watch Dogs series, on PC. I’m certain I spent more time than the average player in the first two games, having played through both twice, going for the completionist approach the first time I played both of them, and having spent more time than I’d like to admit in the multiplayer modes of WD1 and WD2. By “completionist approach,” I mean getting the progression meter to 100% in the first game, and going for all the collectibles spread around the map in WD2, in addition to completing all the missions. Why? Because, in general, I found their gameplay and virtual worlds enjoyable, regardless of their story or general “theme.”

While players and Ubisoft marketing tend to overly focus on the “hacking” aspect of the series, in my opinion its most distinctive aspect, compared to other open world games, is the fact that more than being a shooter, these can be open world puzzle games, requiring some thought when approaching missions, especially when opting for a stealthier approach. Mainly in the most recent two games, and to some degree in the first one too, there are typically multiple approaches to completing missions, catering to wildly different play styles. This extends even to their multiplayer aspects and adds to the replayability of the games. For example, I went for a mainly “guns blazing” approach on my first WD2 playthrough and settled with a “pacifist” approach when I revisited WD2 for a second time – which, in my opinion, is the superior way to get through the game’s story. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Initially, I was going to write a single post with my thoughts about the three games. As I was writing some notes on what I wanted to say, I realized that a single post would be insufficient – even the individual posts per game are going to be exhaustively long. So I decided to write separate posts, in the order the games have been released, which is also the order I have played them. This post will be about the first Watch Dogs, and the next one will be about its sole major DLC, called Bad Blood.

My notes file for the whole series has over 200 bullet points, so hold on to your seats. Before we continue onto WD1, I just want to mention one more thing: I’m going to assume you have some passing familiarity with the three games, even if you have not played them yourself. I won’t be doing much more series exposition; I mostly want to vent about it, not write a recap. Still, I’ll try to give a bit of a presentation on each thing I’ll talk about, so that those who have played the games before can have a bit of a recap, and so that those who haven’t – but for some reason are still reading this – aren’t left completely in the dark.

Onto what is probably the lengthiest ever rant/analysis/retrospective of WD1. Enjoy!

1. Story and storytelling

Diving into the first game of the series, it is the only game in the franchise whose story felt cohesive, without the storytelling feeling rushed or oversimplified. The first time I played the game, I remember going through each mission and wanting to keep playing, much like one never wants to put down a book with an engaging story. In my opinion, it’s the only story in the series that could be written for a book or a movie without it outright resulting in a terrible book or movie just due to story structure and (in)ability to suspend your disbelief.

Compared to the later two games, the WD1 story feels “focused” in a way the others are not. It doesn’t attempt to desperately touch on 10 different present day topics in an attempt to appear extremely up to date; somewhat ironically, this means the story hasn’t become as dated as time has gone by. It also doesn’t try to give as many “in your face” ethics or morality lessons compared the later two games, which is not to say the writers didn’t try to convey messages, it’s just that these are delivered in more subtle ways.

Now, this doesn’t mean the WD1 story is particularly great; more demanding audiences will probably say it’s not even a good one. The first time I played through it, I found it engaging, but looking back, it definitely doesn’t belong on any “best story” award category. The stakes are low, as good writing in video games still seems few and far between.

My summary of the story is as follows: Aiden Pearce, the protagonist, is presented as a hacker with a criminal background that precedes the events of the story. Aiden is motivated by the need for revenge after his niece was killed during a run on him; he wants to know who ordered the assassination and why. In the quest to find out and “fix things,” he ends up involving and killing way more people than necessary. Then, there’s his stereotypical incomplete and half-dysfunctional family, incomplete in big part because of his past actions, and if he’s avenging his family, then he sure doesn’t spend a lot of time with them, really only coming back for them when things go awfully wrong (like, person-is-now-missing wrong). The fact that, at some point in the story, his family must depart to Pawnee never to be seen again, is further indication that Aiden really isn’t helping anyone and realizes that even his family must be protected from him. In the end, Aiden kills the main antagonist, Damien Brenks, and all is well – except, not really, because the city is still full of criminals and Aiden has turned into a vigilante, yada yada yada. There are of course more details and secondary plots to the story, but off the top of my head, that is my impression of it.

Despite the somewhat cheesy, somewhat stereotypical story, I believe Aiden Pearce is, by far, the best protagonist this series of games ever got. Like Niko Bellic from GTA IV, it was designed for a gritty and serious story, and the fact that you can do some deep analysis of this character is already an indication that more thought went into it than into most of the characters on the remaining games. Other WD1 characters, like Jordan, Damien and T-Bone, are also memorable and “seriously written,” with the story allowing proper character development.

The story is divided into missions, grouped in a total of five acts plus an epilogue. There’s a total of 40 main missions in the game, but while Act II has 15 missions, Act V and the Epilogue have just one. Each main mission must be completed before progressing to the next one: the story is fully linear and there are no branches or alternate story lines.

Pacing-wise, in my opinion the latter half of the story and missions feel slightly rushed, as if after the initial missions were done, the developers realized that the remainder of the story had to move faster for the game to not be too long, or the most likely reason, which is that the development of the game itself had to be rushed. You can even see an uneven distribution of mission counts between “acts,” with the latter ones having fewer missions; while this could definitely be a deliberate choice, I stand by my word that the gameplay and story feel less polished towards the end.

One must wonder if the main reason for the serious and darker tone of the story was because Ubisoft drew inspiration from the latest successful open world games at the time, in particular, GTA IV, Red Dead Redemption and Sleeping Dogs, which had more “serious”/”cinematic” stories. By the time GTA V came out with a story that took itself less seriously and which had clearly more of a “mocking” tone than a “serious” one, the WD1 story and ambience must have been set in stone already, with the game well into development. Interestingly, in WD2 Ubisoft went for a very different story tone than that of WD1, perhaps just to make it even more distinct from what was perceived by many as a failed game, or maybe as a bit of a reaction to the “always sunny” GTA V.

I’m sure multiple people have critiqued the WD1 story way better than I ever could. Personally I don’t even pay that much attention to the story when I’m playing this kind of games, and only really thought about it after reading different (disagreeing) reviews and comments. The story in GTA V is flawed too, and games like Just Cause, for example, have almost no story – that doesn’t stop them from being great games on other merits alone. The way a story is told goes a long way towards our perception of its quality.

WD1 is the only game in the series that seriously attempts to be “cinematic,” and sometimes manages to actually pull it off, without resorting to being a collection of cutscenes with fixed gameplay, which is how I would describe much of the mission design in GTA IV and V. In big part, the game achieves this by using well-designed camera settings that put the player very close to the action while also placing the protagonist off-center when there are fewer things going on. Speaking of cameras, the camera movements when “camera surfing,” i.e. hacking into the cameras around you and going back to your normal character view, are also extremely well designed aesthetically and generally work well gameplay-wise.

Not allowing missions to be replayed while simultaneously having a single save slot is one of the failures of WD1, drastically decreasing replayability for those willing to relive parts of the story but who have insufficient time or motivation to commit to a full playthrough. The only way to replay missions is by starting from scratch, or by manually copying your save file after every mission and later restoring the save file for a particular mission. This is a problem fixed in WD2, where missions can be replayed after completion and there are three separate save slots. Sadly, to my knowledge this is something that not even modders were able to fix in WD1.

2. Open world

Watch Dogs takes place in a “near-future” – for 2014 standards – creative adaptation of Chicago and its suburbs, where a pervasive surveillance and control system produced by the fictional Blume Corporation has been installed – ctOS. It is simultaneously Aiden’s biggest intangible enemy and also its best ally, as many of the hacking opportunities come through vulnerabilities and backdoors in ctOS. The game appears to take place in the autumn, as tree leaves are yellow-brown and days are not particularly long.

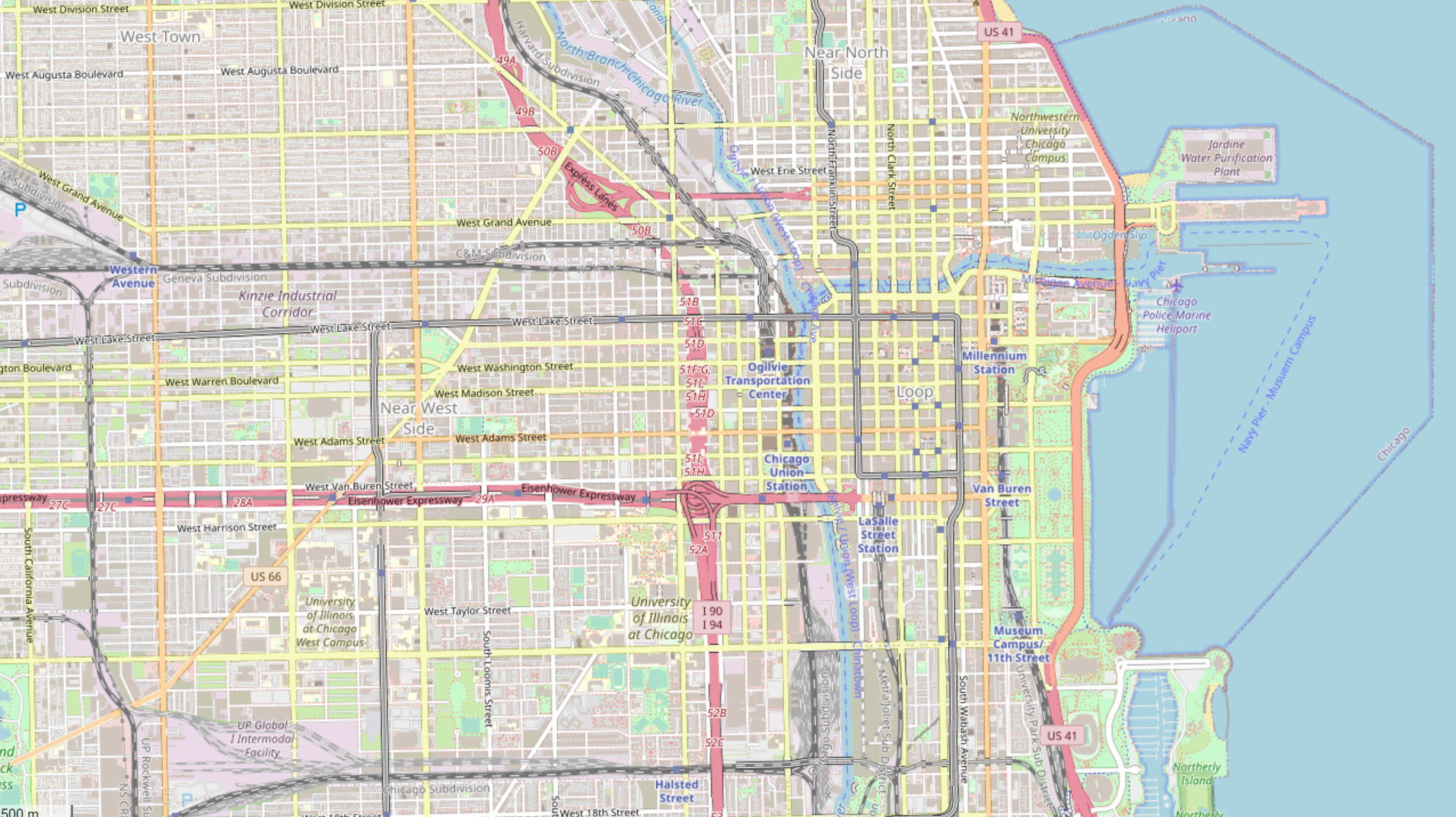

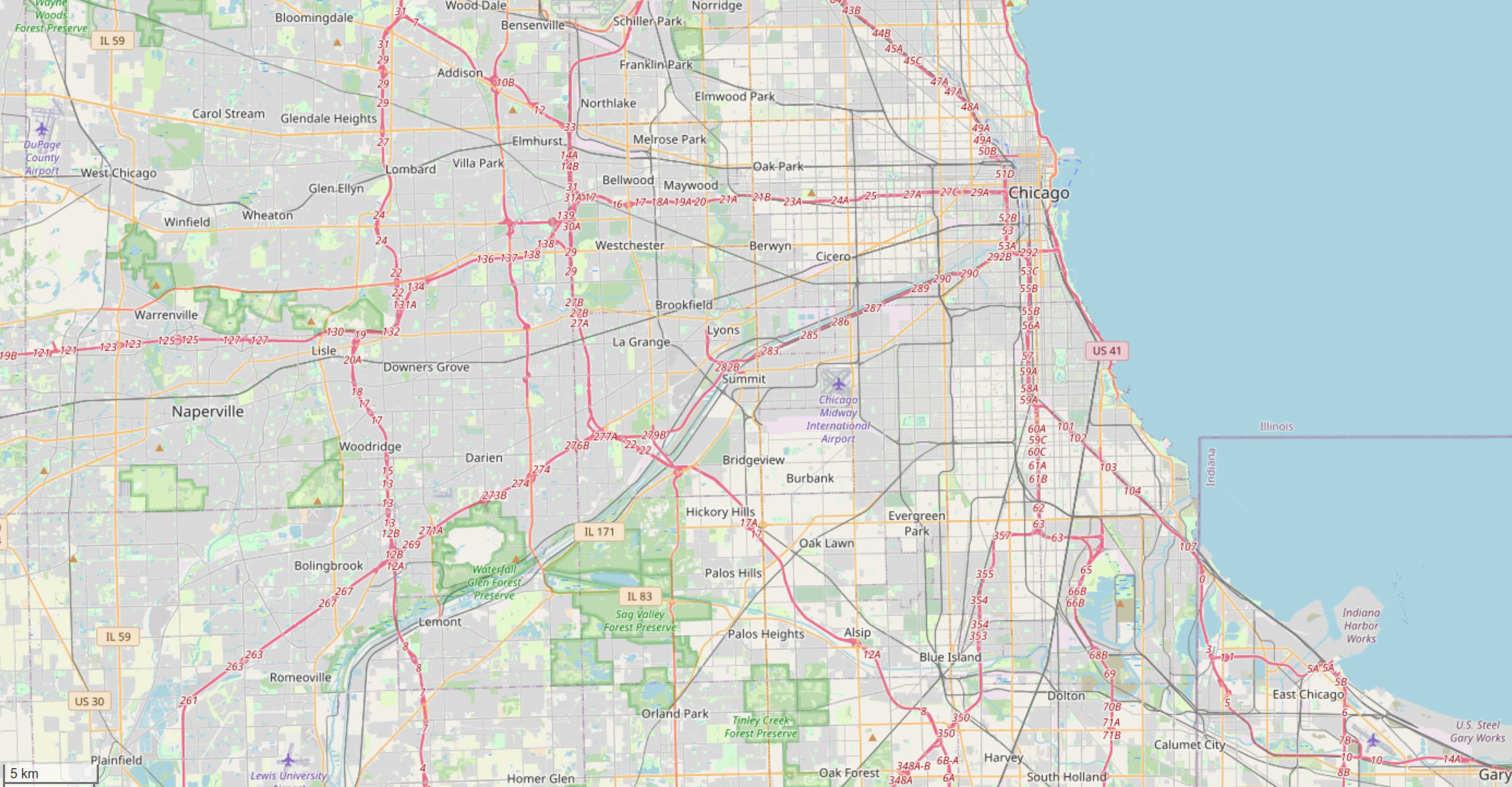

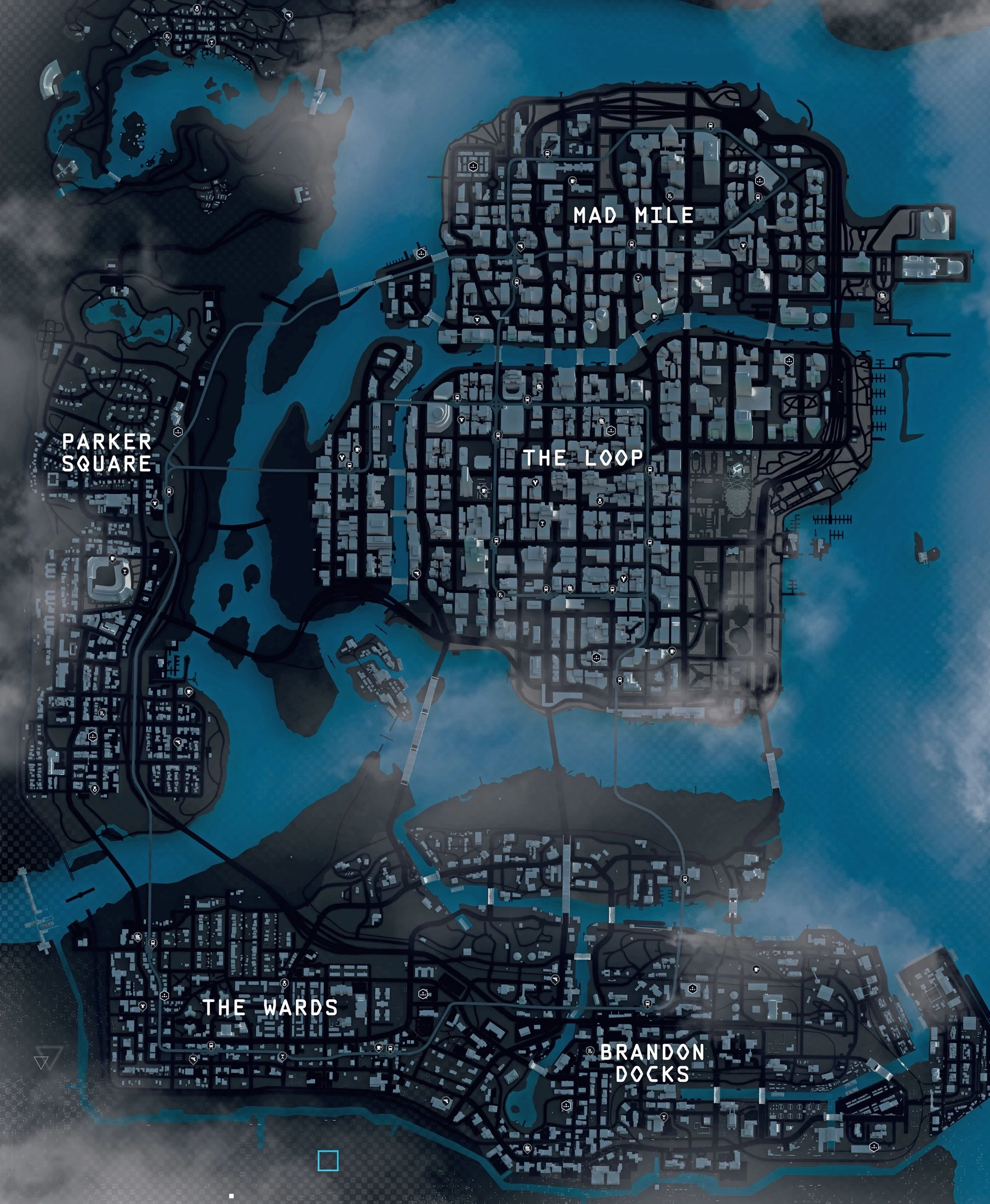

The game is extremely forthcoming about the fact that its world is meant to represent Chicago, referring to the city directly by its true name and sometimes also by its “Windy City” nickname; multiple attractions and landmarks have the name of their real counterparts. However, the physical layout of the world, especially as one moves away from the city center, has less and less to do with the real life city/region it is meant to represent, and even in downtown Chicago, the proportions are all wrong. Someone who played WD1 and never looked at Chicago on a map might believe it is surrounded by much more water and much larger water canals, like New York, than it actually is; many location names and even their features are largely made up (e.g. there’s nothing like Pawnee northwest of Chicago). In this front, while the world of WD2 is almost a virtual trip to the Bay Area, WD1 is more of a fantasy world that happens to have Chicago-inspired architecture and landmarks.

Setting aside comparisons with real world locations, the WD1 world is nice-looking, detailed and relatively big, but suffers from telltale signs of faking its own size, attempting to appear larger than it actually is: roads with more curves than they should (particularly in districts other than The Loop and Mad Mile), distances that are noticeably not very life-like, inaccessible locations and missing shortcuts to forcibly make trips longer, notably on the way to Pawnee. But when we look at the map from above, it isn’t actually that small. Perhaps the feeling of the world being artificial is mostly a failure of Ubisoft’s world design guidelines or editor tooling.

There are multiple world areas and elements that reek of “copying and pasting” in a way not seen in the open worlds designed by Rockstar – mostly because Ubisoft definitely used much more automated and streamlined processes for world building, with lower prop and model variety. This let them build worlds faster, and so we got three Watch Dogs in the span of one GTA and one RDR – tradeoffs, tradeoffs. To a degree, the “fake distances” and the somewhat frequent asset reuse make the game feel previous gen, and can make sightseeing a less appealing activity.

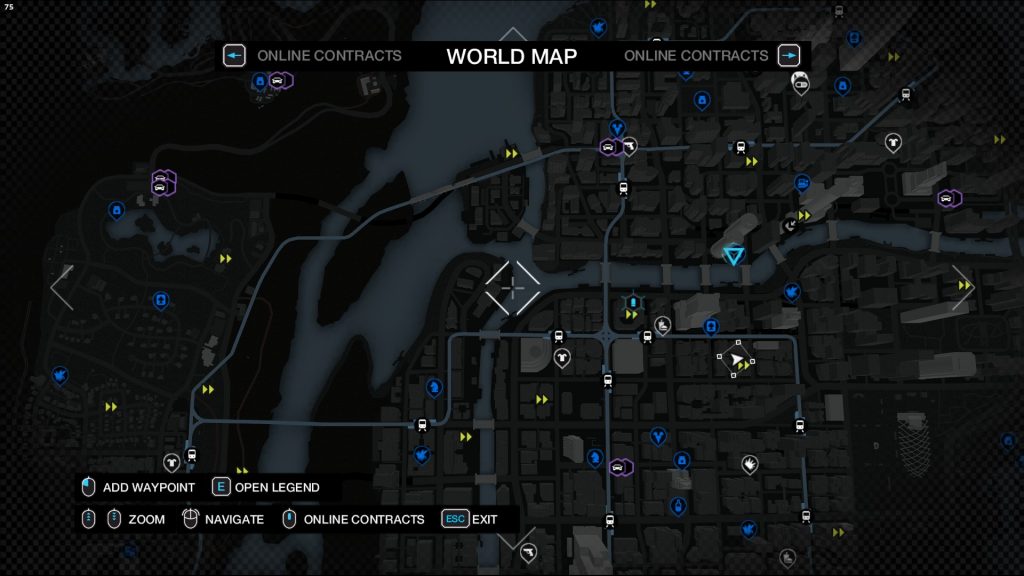

Note: there are slightly more elements in the map than usual, as I have the Living_City mod installed.

The game also attempts to make most roofs inaccessible, and with Chicago having so many tall buildings, it really feels that verticality is not properly explored in the game’s world; perhaps this was an artistic choice – and a convenient way to ease the trouble of dissimulating world boundaries. This has the unintended side effect of turning roof climbing into a secondary game of sorts; the perfect thing for players who generally enjoy “breaking the game” by going out of bounds. There is, or was, at least one YouTube channel focused on showing how to climb most of the roofs in WD1. This has interesting implications for certain multiplayer modes, as I’ll explain later.

In the “living city” department, there’s enough simulated life in WD1’s rendition of Chicago. At least on PC, crowd and traffic density is more than acceptable – to the point where, in narrower streets, it sometimes feels like there are more cars than what would be convenient in terms of gameplay. NPCs react to player actions and to the environment in predictable but entertaining ways. Random police and firetruck chases spawn here and there, and “vigilante events” also spawn randomly at preset but undisclosed locations – more on that later, once I talk about the Reputation system.

There aren’t a whole lot of always-available interiors, and even the big stadium of the initial mission becomes largely inaccessible, but you can go into bars and coffee shops to drink something. Nothing groundbreaking here, but for a 2013 game, I think it doesn’t fall short of expectations. And with mods, you can improve on this aspect of the game by not only adding more random events, but also making more interiors available outside of missions.

“The L” – the metro train system – provides a different way to traverse the world while giving the player a slightly more elevated (heh) perspective of it, but in my opinion, it still isn’t enough to provide the lacking “verticality.” It gives fans of public transit systems something to appreciate and yet another hacking target, and by that I mean that you’re able to stop and start each train near you; the system still attempts to prevent collisions and even if you manage to override this, trains will just phase through each other.

The player can move around inside and across train cars even as they move, which is much more immersive, and technically impressive, than GTA IV’s subway. Besides sightseeing and amusement, the trains are not just decorative, as they provide an alternative way to escape police and enemy chases. Overall, it’s a well-implemented world element, and certainly better than the almost-complete absence of the Underground in WDL’s rendition of London.

3. Gunplay and mechanics

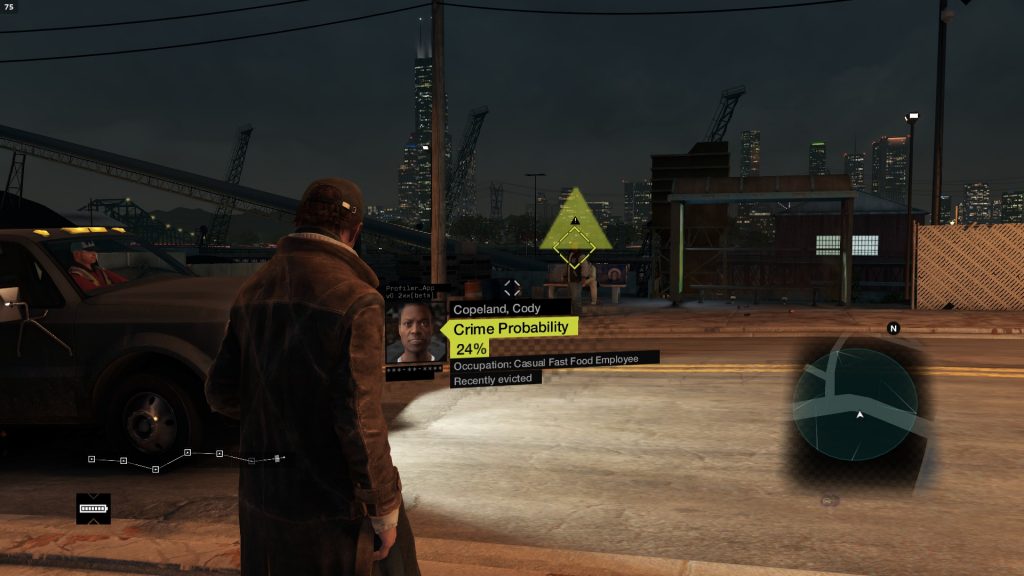

Getting the elephant out of the room, the most thematic, novel and pervasive game mechanic in WD1 is, of course, hacking. This primarily happens through the “Profiler” – a HUD mode where you can aim at the faces of NPCs and different devices present in the world and see some information about them. Some devices can only be “hacked” when the profiler is active. For NPCs, a random “fun fact,” such as “Attended furries convention,” and their age, occupation and income are generated and displayed. Some of them are fixed for special/mission-specific NPCs. Like devices, sometimes NPCs can be hacked too, which lets the player see one of a few dozen possible text message threads, or listen to one of a few dozen possible phone calls, or, more interestingly, one can hack some NPCs for money, which then needs to be cashed out at an ATM, at which point it actually becomes spendable in-game.

Different elements of the world, such as cars, bridges, metro trains, traffic lights, steam pipes, explosives, forklifts and blinds can be hacked, which is to say, they have a single action associated with them which you can perform by opening the Profiler, aiming at them and pressing the key or mouse button that you’ve bound to the “hack” action. The action happens immediately and destructive hacks, like exploding a steam pipe or detonating an IED, can only be performed once (of course, world elements like steam pipes repair themselves once you get sufficiently far away).

With some patience, this kind of environmental kills can be used to get rid of a few enemies on a given area, but I think they feel less and less rewarding over time – waiting for an enemy to get close to your “weapon” so you can then hack it takes a lot of patience, and in most levels, not all enemies can be dealt with like this. Many hacks also consume the phone’s “battery;” as you progress in the game, you can make your battery larger so you can hack more things without having to wait for the battery to “recharge.” But the cool-down on this sort of lethal hacks means that using them to clear levels requires even more patience.

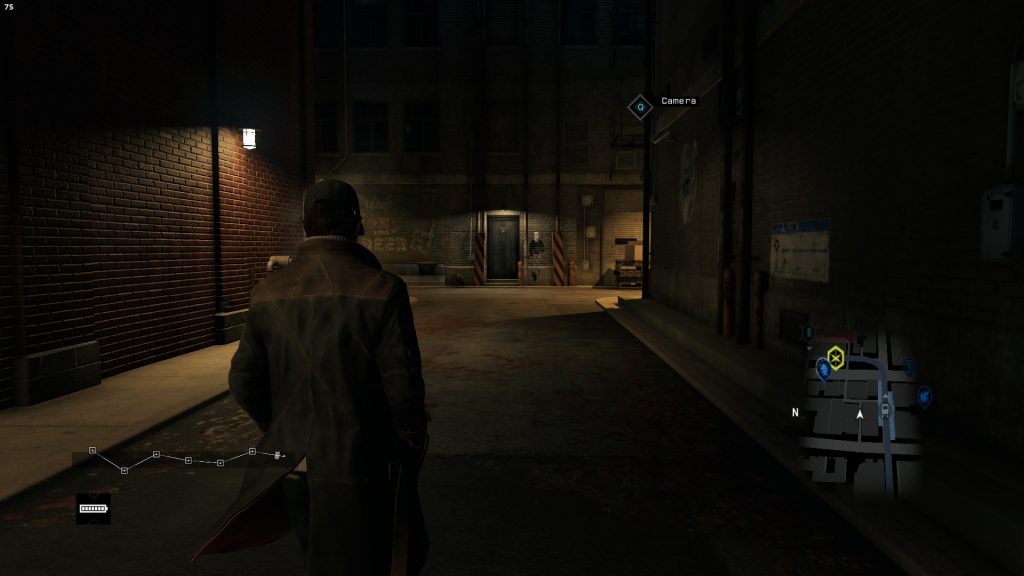

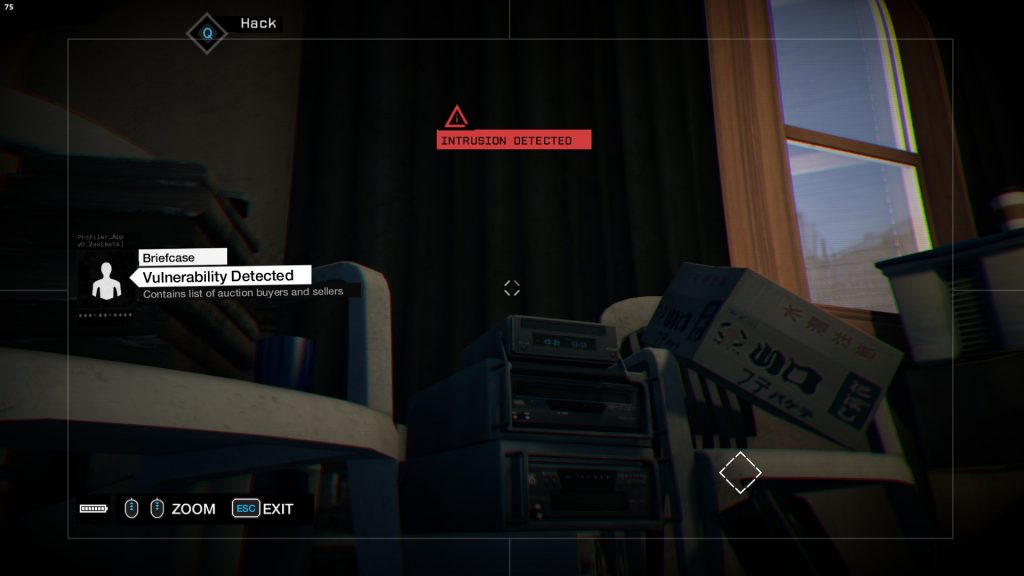

There are many CCTV cameras in the world, which can also be hacked to look through them, at no battery cost. From the view of a camera, you can hack other items, including other cameras. You can therefore navigate through cameras, up to a certain maximum distance, and use this to look into and mess with areas where Aiden is not present. It’s a feature clearly intended to let you recon enemy ground before moving, in addition to being an essential tool to solve some “puzzles.” In WD1, which lacks tools like the drone introduced in WD2, cameras are the only way to look and interact with things beyond one’s immediate vicinity.

While driving away from enemies, a sort of quick time event can occur, where if an enemy vehicle is crossing a junction with traffic lights or going over an underground steam pipe, the player will be prompted to quickly press the hack keybind in order to destroy the enemy vehicle – and sometimes their own, if they happened to be too close to the steam pipe that the other vehicle was going over. The effort the game makes to be cinematic is visible here too: sometimes, when the attack is successful, the game will slow down slightly and turn the camera towards the destroyed enemy vehicle for a brief period, before resuming the normal orientation. If one’s not looking, the game will even “cheat” at this and spawn vehicles at junctions (and direct enemy vehicles into obstacles) so that traffic light hacks are more successful at crashing vehicles, as long as the player had the right timing.

There are also some world status effects the player can apply, which fall under the “hacking” umbrella. Players can trigger blackouts, or jam coms to prevent enemies from calling reinforcements, for example, through consumable items accessed from the weapon wheel. Blackouts can also be triggered by crashing into certain utility poles and junction boxes. These effects last 15 to 20 seconds before they automatically disengage.

To “hack” certain devices and progress through key story points, players must solve maze-like puzzle minigames that typically appear once one attempts to hack a device like a “network hub.” In these puzzles, “Energy” flows from one or more source points in a “circuit,” and corners and junctions of the “circuit” must be rotated, sometimes in multiple different steps and unlocking intermediate circuit pieces, until there is a path to the destination. In WD1, these “circuits” are laid out in a dark, empty 3D space that takes over the whole screen as the puzzle is solved. The difficulty of these puzzles increases as one progresses in the game.

For the most part, hacking in WD1 is a one-button mechanic that often has very little strategy involved, and has very little to do with any real-life cybersecurity activities. Still, I understand that the game developers’ main idea was to bring awareness to how more and more things in our real world are network-connected, and how vulnerabilities in computer systems can have drastic real-life consequences and be used for nefarious purposes. Managing to integrate that as a fun and simple game mechanic is commendable; I think that trying to criticize the game for not being realistic in this regard reeks of pedantry.

Beyond hacking mechanics, let’s talk about one mechanic that requires an even stronger suspension of disbelief: the Focus ability. Commonly also called “bullet time,” it lets the player slow down time at pretty much any moment, highlights enemies in the world, allows Aiden to move sideways while on foot, and to take tighter turns while driving. The ability is toggled on and off using a key or mouse button, and having it engaged depletes the Focus meter, which appears in the HUD when focus is enabled. With this ability fully upgraded, the meter takes 7 seconds of real-world time from full to empty. Focus recovers slowly when not in use, and it can be temporarily slightly improved by using the Focus Boost craftable, or by visiting cafés and purchasing drinks.

I found Focus to be an entertaining mechanic that can sometimes make the game a bit too easy. It is much easier to aim for the heads of enemies with Focus engaged, and precision driving also becomes a walk in the park, in fact, it is the only way to take tight corners at high speeds. You can only use so much Focus before you have to wait for it to regenerate, but since effective use of this ability consists on engaging it for brief moments at a time, this doesn’t really matter – it is still a bit overpowered. Focus works but doesn’t slow down time in multiplayer sessions: this has implications for certain online modes, as I’ll explain in the respective chapter.

Focus is certainly not an essential or game-defining mechanic; it’s yet another thing for the player to remember they can do. WD1 would not be a worse game if this ability was missing, but it just looks cool – there is no denying that it contributes to the aforementioned cinematic qualities of the game. Subsequent titles have no bullet time ability.

Moving on to less unique game mechanics, I found that the gunplay and weapons range from “adequate but unremarkable” to “I’ll make sure not to use this weapon again,” or in other words, they are another “ok” aspect of WD1. Ideally, this wouldn’t be much of a problem in a hacking-focused game, but with a lack of non-lethal options for completing missions, one ends up being always playing the game as a shooter with “hacking” being strictly an accessory that, in most scenarios, will not deal with more than half of the enemies in each situation. I suppose that, if you go through way too much trouble (putting many times more time/effort than normal to complete each mission) you can place lures, explosives and use hacking-based environmental kills to deal with even more enemies through “hacking,” but in my opinion it is clear that the game was not designed nor calibrated for this.

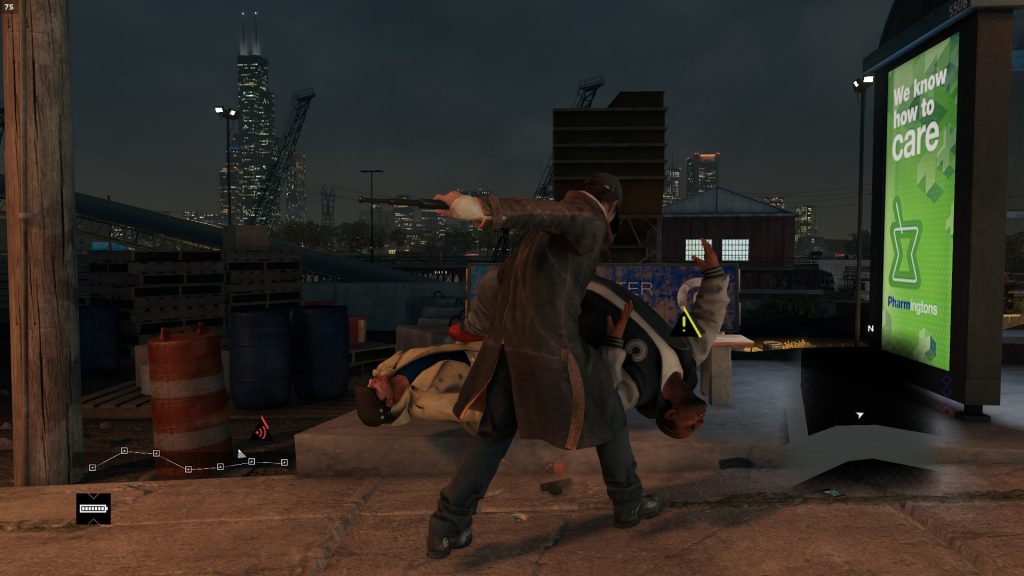

The more realistic options to clear levels are to use weapons or to go for melee kills – “takedowns.” The latter option can be quite entertaining and even “cinematic” (the animations are great and definitely help with this), but it still feels like a lethal, havok-wrecking option. Still, the gravity of the main character’s actions, even in a full guns-blazing approach, fits relatively well with the tone and setting of the story, but then we shall judge the gunplay as a primary element of the experience and not as an optional element of the game.

Gunplay doesn’t feel exceptionally good but it is on par, perhaps even better, than comparable open world games. Each gun feels different, but mostly just because of recoil effects that felt mediocre to me; the sound effects are good but repetitive, which can break the immersion for those used to more realistic shooting mechanics. Some weapons take more skill to use because of strong recoil combined with small magazines, but with the exception of weapons that do things no other weapons can do (as is the case with grenade launchers), I don’t feel the game provides enough motives to use more difficult variations of weapons within each category – you’ll always want to use the best few assault rifles, the best shotgun, etc.. Recoil patterns appear to be somewhat random, but I’ve noticed that there appears to be a general bias towards the right and towards the top, with some weapons being more biased towards one of these directions than others.

I suppose the existence of inferior weapons provides a sense of progression as you’re able to get a hold of better ones, but the truth is that once you find some that work for you, you probably won’t want to exchange them. This is visible in the online modes where you’re allowed to choose your weapon – people tend to “main” just one or two of them, and it’s usually either the grenade launcher, or the overpowered sniper that kills any player or vehicle in one shot. One always carries all weapons they’ve unlocked so far, which means your not-favorites are there mainly to annoy you, if you select them by accident on the weapon wheel.

Unsurprisingly, most weapons, with the exception of the grenade launchers, use hitscan. There is aim assist on console (and, I believe, on PC too, if you use a controller), but I primarily aim using the mouse so I won’t comment on that. One anti-feature that annoys many players is the forced mouse acceleration when aiming, which can’t be disabled in any way. Honestly, I never noticed this until it was pointed out to me, but the fact that I’ve always enabled mouse acceleration outside of games might have something to do with this.

Players can also throw grenades, proximity-activated explosives, manually-activated explosives, and lures. The latter two are activated upon hacking them, which means that they need to be in your (or an accessible camera’s) field of view in order to be useful. Lures are used to attract enemies to their location. The four throwable devices can be purchased at a specific in-game shop, or “crafted” through the weapon wheel.

Despite not being necessarily oriented towards stealth or pacifist gameplay, WD1 punishes unwarranted violence. In addition to the somewhat infamous Reputation system that I will analyze in the next chapter, simply visibly holding a gun will get Aiden noticed by civilians around him, and just aiming it randomly can be enough for those civilians to begin calling the authorities – calls which you can interrupt in a variety of ways, like using the Jam Coms hack. The same applies when driving recklessly and harming pedestrians – calls to police will begin much earlier in the chaos than in GTA titles, for an immediate comparison with another game that puts emphasis on police chases. My impression is also that police is much more brutal and accurate with their shots, even at lower heat levels, than the cops in GTA V. In accordance with Aiden’s character design, tolerance of violence and random antics in WD1 appears calibrated towards a more serious and pacific role-play, when not in enemy combat. Therefore, in comparison with other role-playing action games, WD1 is not particularly welcoming to those looking for a chaos&mayhem sandbox.

Player movement and animations are good, with the “parkour” (or as Ubisoft calls it, “freerunning”) being especially good. Personally I find the cover system very good and predictable, compared to other contemporary open world shooters. It is easy to know where you are going to take cover, it’s easy to change cover positions with precision, and one rarely gets out of cover by accident. In a way, this makes up for any gunplay weaknesses – if you don’t like the weapons, you can just take your time with them by playing more defensively. Just beware that usually enemies won’t stay on the other side of your cover forever, and will actively try to reach you.

Functionality-wise, I have no complaints about the game’s HUD, at least, I don’t remember having any particular frustrations with it. It shows the status of your weapons just fine, the destination of your throwables, your “smartphone battery” and Focus meter levels, as well as the minimap with Aiden’s heat level below it. Of course, more temporary stuff also shows up, including mission objectives, reward/looting information, online matchmaking status, and notifications for nearby crime activity and “items of interest.” All of these things appear and disappear as needed, except for the battery level and minimap which show at rest. The majority of the UI interaction happens through the “smartphone,” the map screen and the weapon wheel, and there’s also a pause menu, that lets one quit the game or the current mission, as well as enter the settings menu.

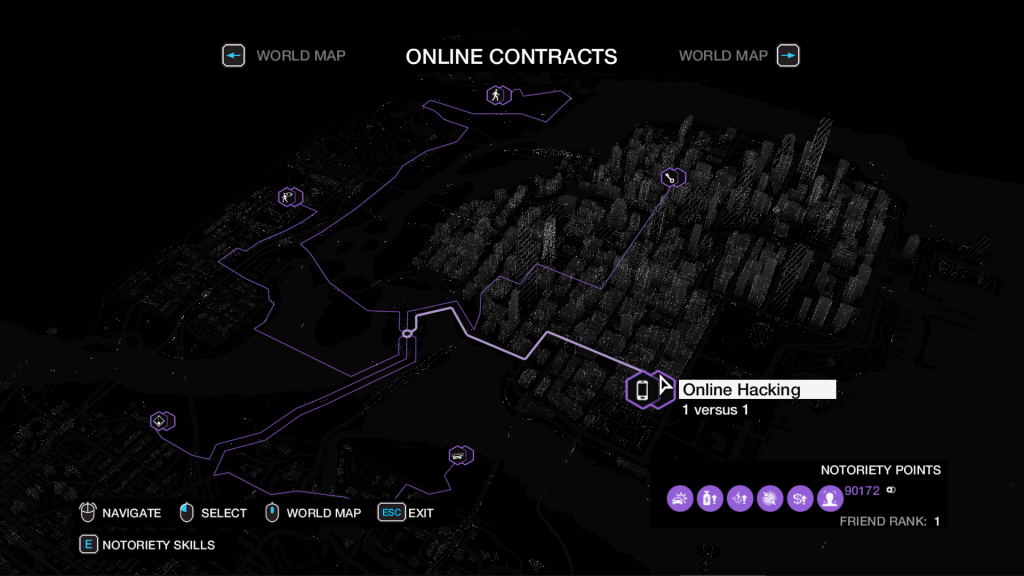

When open, the smartphone menu is overlaid on top of the gameplay camera, and takes up the majority of the right hand side of the screen. You can access pretty much all game features from it, including setting your way to most side-missions, accessing online leaderboards, controlling the “music player,” spawning cars on demand (subject to a number of restrictions), and seeing information about the current online session. The smartphone also provides a shortcut to the “online contracts” section of the map screen, which lets you launch multiplayer modes. The main section of that screen is just the regular world map, with 3D building outlines; from it, you can set waypoints and fast-travel to hideouts.

The weapon wheel, in addition to letting you select the active weapon, also lets you select which throwable item is active (among grenades, IEDs, lures, etc.) or, in alternative, which world effect hack (blackout, jam comms, etc.) is selected to be triggered on demand. It is also from the weapon wheel that you craft these items from components. This technically makes it so that the game has a crafting system, but it is so basic – a single wiki page is enough to describe it – that it won’t annoy those who dislike crafting mechanics, without satisfying those who like them either. In short, it doesn’t make anyone happy, so I wish it wasn’t there at all.

The HUD can be a bit busy especially when different kinds of notifications appear; fortunately, opening the smartphone or the weapon wheel hides other HUD elements, otherwise it’d be even messier. I suppose that this busyness can also be a conscious design choice, to be reminiscent of the extremely busy screens hackers always have in movies.

Overall, the UI could definitely be simpler, more straightforward. Some options are present in the smartphone, others require heading to the world map, and another set of them, like quitting missions, are available from the pause menu instead, which can make things a bit confusing, but not more so than what you would see in other games of the era, including GTA IV and V and Sleeping Dogs. Years later, WD2 would do a better job of presenting the map as yet another of the smartphone’s features; it also moved multiplayer mode selection off of the map screen, and added a shortcut to the pause menu (“Game options”) to the smartphone – so that players can always find a way to everything from a single menu.

4. Stats and progression systems

I am going to be using a very lax definition of “progression system.” Some of the things I’ll mention work definitely more like “stats” or could simply be called “game mechanics,” but for the sake of simplicity I’ll mention them here.

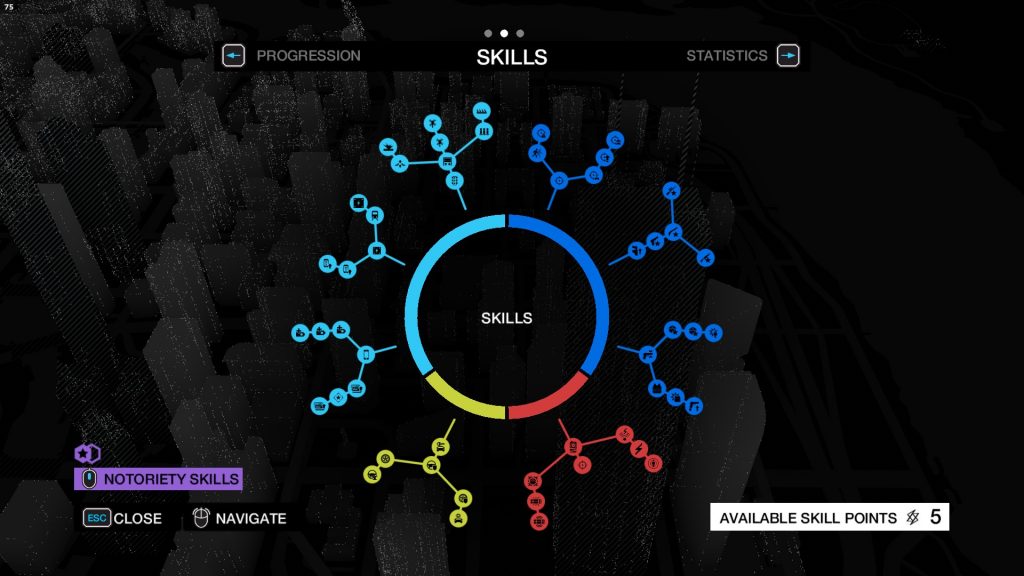

The XP system is the main progression system in WD1. Experience points can be obtained by taking down enemies, completing key objectives, completing missions, that sort of thing. Earning XP lets one increase their XP level and at each new level you get skill points, which can be spent on the skills tree, the system that lets one upgrade Aiden’s abilities. Skills are divided into four categories (Combat, Crafting, Driving and Hacking) and within each one there are some dependencies, i.e. skills that must be unlocked before you can unlock others. The maximum level is 50, past which you don’t accumulate any more XP or levels, and by extension, there’s a cap to how many skill points one can earn. I wish this wasn’t the case, such that the XP level could be used as a metric of how much you’ve played compared to other people, even if no additional rewards were unlocked after level 50.

Skills do things like reducing weapon recoil and making Aiden more stealthy, or resistant to damage, or able to hack more of the world’s devices; Focus is another of the abilities unlocked through the skills tree. You can’t undo spent skill points – there’s no way to reconfigure your character mid-game by reassigning your earned points. As you progress through the game, you’ll eventually earn sufficient points to unlock all the abilities, so it really is a matter of deciding which skills you want available sooner. While this eases the mind of undecided players, it also means that by the end of each playthrough, any player’s Aiden can do pretty much the same as any other. It’s not like some more role-playing-oriented games, where one kind of has to choose a “life path” for their character leading to different abilities and playing styles.

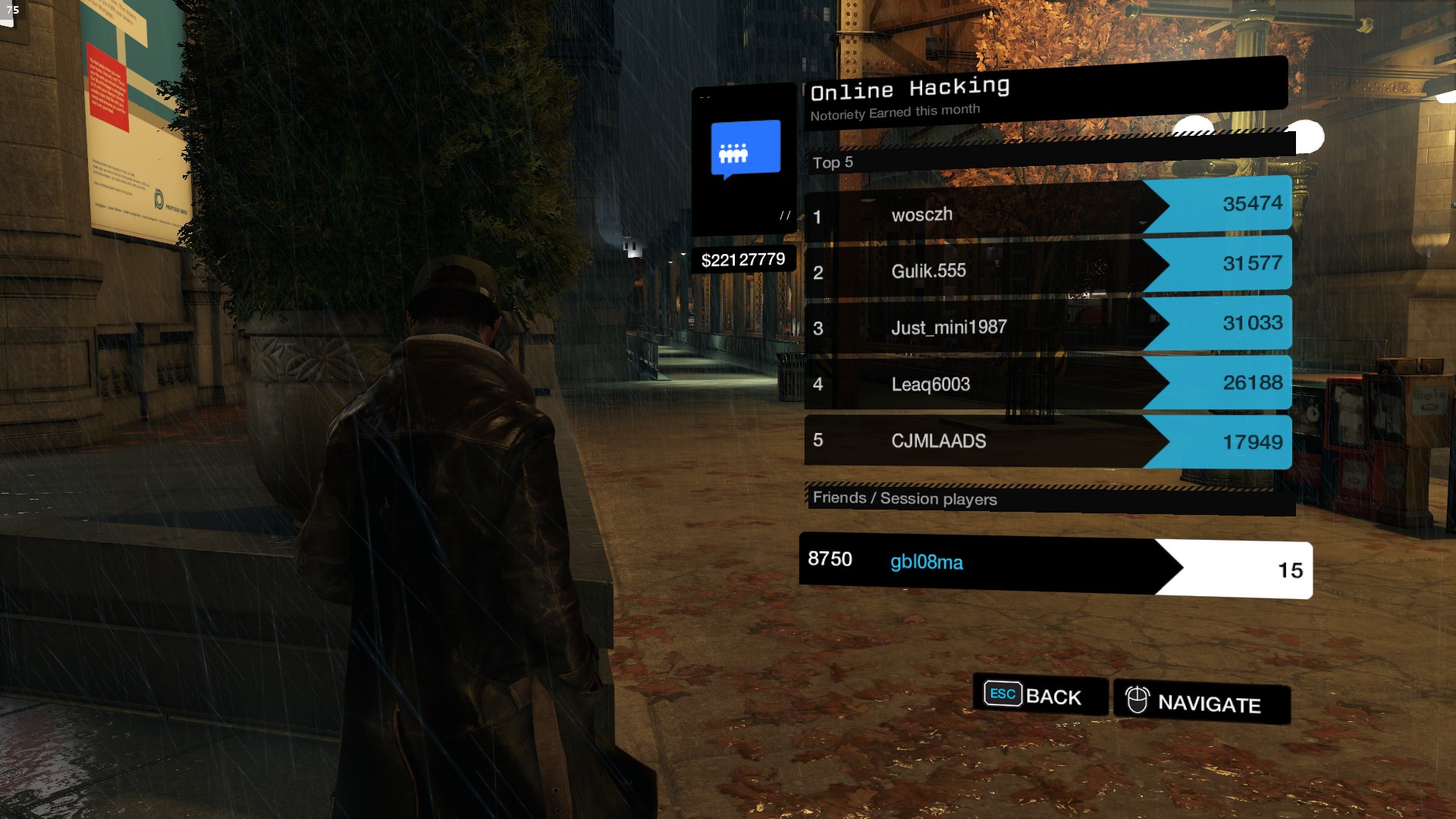

In addition to the skills tree, there are secondary progression systems that grant abilities as well – like the skills tied to Online Notoriety, a stat that I’ll briefly discuss in the multiplayer section. Certain minigames also have their own skill trees, and so does the “Street Sweep” series of side-missions from the Bad Blood DLC, that I’ll discuss in a future post.

Like in many open world games, the player also has a money balance. The fastest way to increase it is by hacking civilians with fat bank accounts and then withdrawing the cash at an ATM – which incidentally means there are two money balances instead of one, the “normal” balance and the “unclaimed hacked bank accounts” one. More… conventional means to get money also exist, like robbing stores or by playing certain minigames. Money can be spent on ammunition and crafting components, outfits, vehicles, weapons, and other minor things. There is nothing surprising here, but it’s yet another stat that the player needs to be aware of.

Another stat system in WD1 is the “Reputation,” a value which represents how the society of Windy City sees Aiden Pearce. This is a value that can either be positive or negative and which is controlled by the actions of the player in the game. “Bad deeds” such as hurting cops and civilians lower your reputation, and “good deeds” like catching criminals increase your reputation. The reputation doesn’t have any effect on how the story progresses or on Aiden’s abilities, but if you have negative reputation, your gameplay will be interrupted by news broadcasts reminding you of how much of a menace your Aiden is and you’ll hear NPCs on the streets bad mouthing him; if you have positive reputation, you’ll overhear them praising him.

I found the reputation system to be terrible, more of an annoyance than anything. Without any mods installed, there is a variety of ways to lower your reputation – namely, accidentally killing civilians due to the tricky vehicle physics – but increasing your reputation takes much more effort. Completing missions increases your reputation, but when you’re done with all the missions, the only way to increase it will be through waiting for the randomly spawning “vigilante events,” where you’ll be able to take a criminal down. (No, don’t just take down any civilians the Profiler tells you happen to be criminals – those will count as homicides and lower your reputation.) These events end up being repetitive, and not that engaging, so over time, especially if you continue to play past the main story (e.g. through the multiplayer modes), your reputation will most likely trend towards the red, as unlike what happens with “bad deeds,” there aren’t really any “good deeds” you might do by accident.

Considering how annoying it is, it’s probably for the best that the Reputation doesn’t have any impact on the story progress, nor on any mechanics beyond those of the reputation stat itself. At the same time, the inconsequentiality of this stat also makes it all the more annoying, as it ends up being mostly just a stain on the user experience – randomly receiving a repetitive news broadcast about how much of a menace you are isn’t exactly fun nor immersive past the 3rd occurrence. Ubisoft certainly recognized this in retrospect, probably after dozens of players pointed out what I just said, and reputation-be-gone from WD2 and WDL.

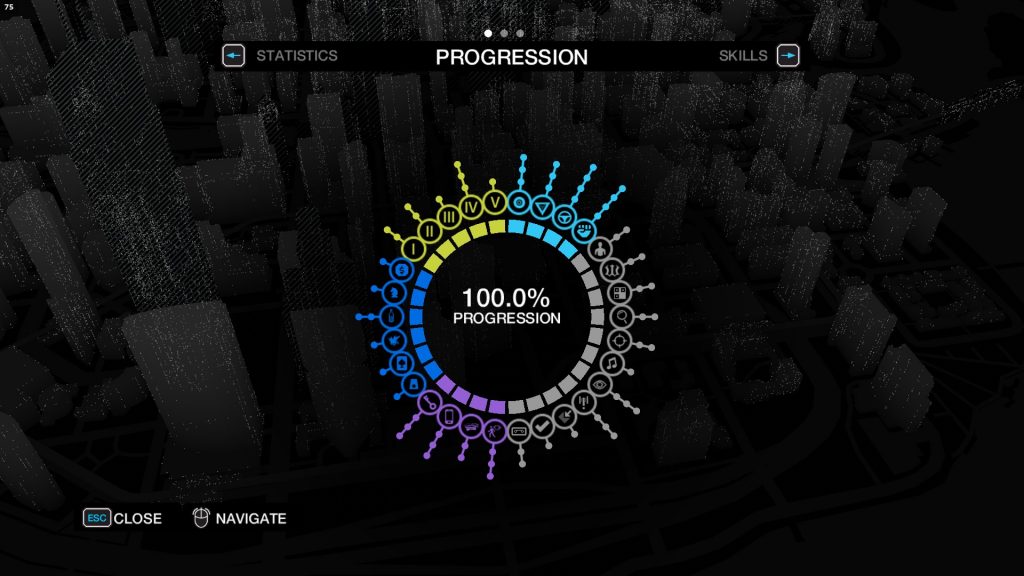

In addition to XP, Reputation and Online Notoriety, the game collects a series of stats. Some of these are visible through the Progression Tree, which is really just a summary of one’s accomplishments in the game. In addition to story progress, it tracks collectible counts, side mission completion, and the minimum numbers of online missions completed in order to obtain certain trophies.

Overall, in typical Ubisoft open world game fashion, I found that there were perhaps a bit too many stats to keep track of. The different numbers and progression systems can give an appearance of complexity, even if in the end only the skills tree really matters. I don’t feel the same kind of confusion or bloat in e.g. single-player GTA titles, even though GTA characters also have multiple stats/skills associated with them which can increase over time. I feel like some of the bloat could have been avoided by letting “skills” be unlocked throughout the story in more subtle ways rather than through a levels system, for example, by granting the ability to hack some device after stealing the “hack” from some facility during a mission, or from a random NPC passing by on the street – although I do admit this latter option could be frustrating.

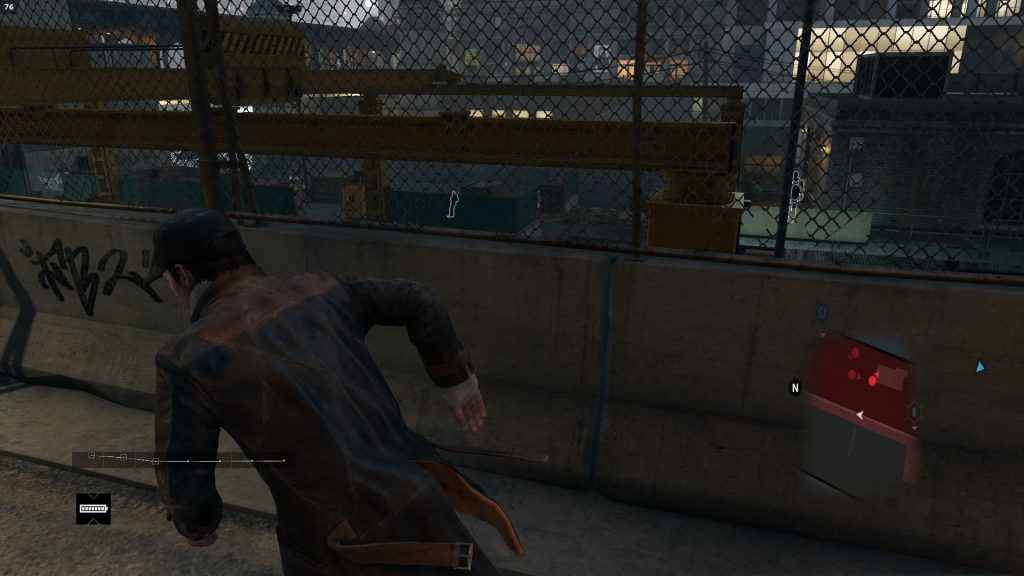

Speaking of typical Ubisoft things on games of this era, I almost forgot something that is halfway between a progression system and a secondary activity: the towers. There are 14 “ctOS Towers” spread throughout the map and unlocking (“hacking”) each usually consists on finding ways to climb buildings and hack devices, basically solve a bit of a puzzle, in order to grant access to the base of each tower, which should then be finally “hacked” to uncover the location of the collectibles in the area covered by the tower. When entering a world area, the HUD reminds you about whether you’ve unlocked the tower for that area by showing “ctOS connected” along with the area name at the top.

Personally, I didn’t find the towers much of a nuisance and I didn’t find them repetitive, as the “in-world puzzles” that one must solve in order to unlock them were sufficiently varied; I think the great environment design, soundtrack and general ambience really helped. Still, if WD1 hadn’t been my first Ubisoft open world, just the recognition of these towers as the overused mechanic would have been enough to decrease their enjoyment. By this time, the public was already mocking Ubisoft for this trope, therefore WD2 would not feature towers like this – and I certainly didn’t miss them, and their absence didn’t make me explore the world any less.

5. Secondary activities and minigames

We already talked about the infamous towers, but there’s more to do besides unlocking them and doing the main story missions. There are multiple side mission series, collectibles, and three different kinds of minigames.

Some side missions consist on a series of very simple, almost single-objective affairs that are mostly disconnected from each other and the main story, as is the case with Fixer Contracts and Gang Hideouts. Others, namely the “Investigations,” consist on multiple mini-story series that are mainly collectible-driven, that is, there is a sort of exposition mission followed by the task to locate a series of collectibles, like briefcases or burner phones spread across the map, and finally some sort of conclusion, which may be a slightly more elaborate mission. In these series that have a bit of a story, those are usually delivered through audio logs and messages associated with each collectible. Side missions unlock different rewards based on many missions of each kind have been completed.

Going into detail about each different side mission series would turn this already length post into a repetition of the different game guides and wiki pages present throughout the web. In case you’re interested in seeing an extensive list, this wiki page is a good starting point, as it lists everything that counts towards the aforementioned progression tree, along with the different rewards.

“Investigations” and “Privacy Invasions” really bring out the darker, grimmer aspects of the WD1 universe. The theme of Investigations is never a light one, from human trafficking to serial killing. One of the Investigations, the “QR Codes” one, is where the most background on DedSec, the hacker group of the Watch Dogs universe, is presented. As for “Privacy invasions,” these are more like collectibles than side missions; they basically consist on hacking into the cameras of strangers’ houses, allowing access into a sort of interactive cutscene for brief periods of time before ctOS kicks one out. They are designed to be provocative and evoke thoughts not just about the dangers of mass surveillance but also about our societies and human condition.

Each type of side missions can be repetitive, but because there are a handful of different types, if one just plays through two or three of each and cycles between them, they won’t be bored. Those that aim for a completionist approach, just want excuses to keep exploring the WD1 universe, or enjoy the combat system in the game, will easily find in these missions dozens of hours of content. Like main story missions, most side missions, with the exception of Fixer Contracts, can’t be replayed on the same game save, in what is an unfortunate limitation. Just because the missions are somewhat repetitive, that doesn’t mean someone with a 100% complete save won’t want to relive them at a later point.

My verdict is that these side missions give the player a lot to do, but few tell much of a cohesive second story, or form any kind of important story arc. Some of them, like Criminal Convoys and Gang Hideouts, can be summarized as “bad guys here, take them out/meet objective X.” Even the more elaborate side missions don’t go beyond side-notes on the main story and the game’s universe, which is perfectly adequate, but doesn’t satisfy those who have a greater demand for well-written stories. Therefore, a distinct sensation that one is playing through filler content may come up every now and then.

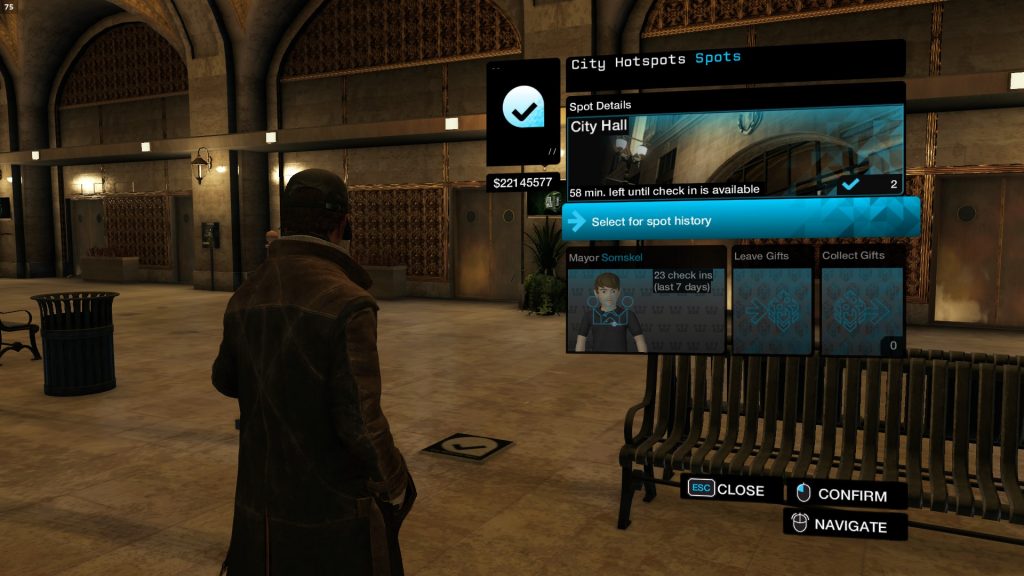

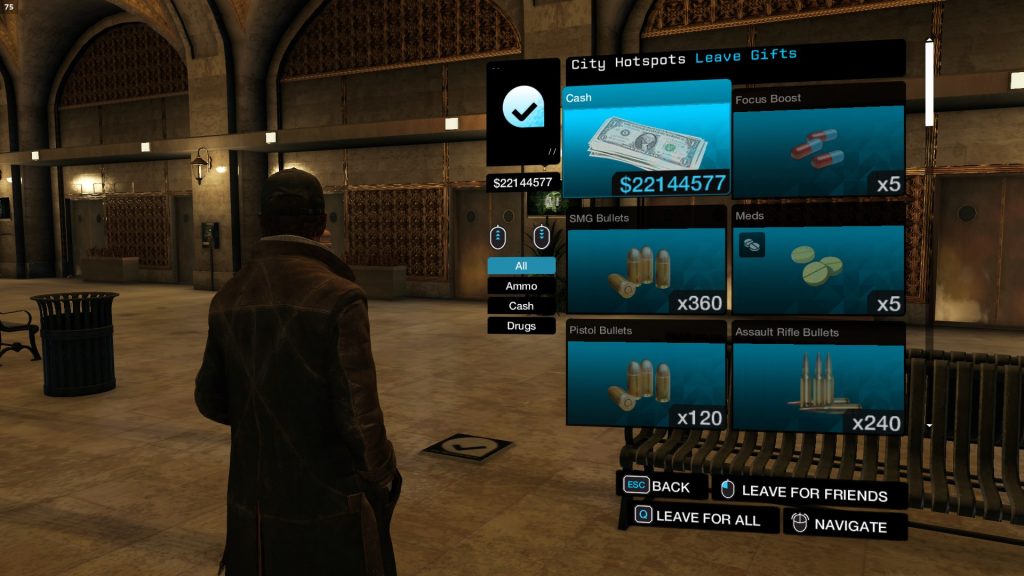

Moving on to collectibles. With this being a Ubisoft open world game, there are many of them. In addition to the aforementioned Privacy Invasions and ctOS Towers, and the collectible-driven Investigations, there are also one hundred City Hotspots (places where one just goes to “check-in;” there are online features associated with them – you can leave items for other players there), dozens of Audio Logs (playable through the smartphone once collected), 16 ctOS Breaches (yet another kind of “in-universe puzzles” involving device hacking, camera surfing and “getting to places”), and SongSneak. This last one consists in the harvesting of songs for the in-game music player from pedestrians, using the SongSneak smartphone app. Somewhat refreshingly, these don’t show up as more map spam: you really need to roam around to find them, which can take an excruciatingly long time. If some side missions could be considered filler content to keep players busy, there is no way these collectibles can’t be considered such as well.

WD1 offers different kinds of minigames spread throughout the map. There are the “conventional” street activities, including chess puzzles, poker, slot machines, shell games and a drinking minigame. Then, requiring a bit more suspension of disbelief, there are “augmented reality” games – Cash Run and NVZN – which take place in the game’s normal universe but with “AR” elements laid on top. Finally, there’s the crazier kind of activity, the “digital trips” available from the smartphone and through street vendors.

The enjoyment one can take from these minigames varies wildly depending on personal taste, but there is no denying that some are more novel than others. The simpler, more conventional minigames like the shell game and slot machines exist more to aid immersive worldbuilding than anything, and might be the result of a “damned if I do, damned if I don’t” decision-making process at Ubisoft; I would go so far as to describe them as “space and time fillers.”

Past open world games had, in a way, set the expectation for the presence of this sort of minigame. If Ubisoft had not included that silly dice cup game in the streets, or the chess puzzles, maybe some reviewers and players would have began wondering and comparing “but GTA IV had bowling… and GTA V had darts…” However, who in their right mind actually prefers playing bowling, darts or chess inside of a GTA or Watch Dogs game? At best, these are roleplay enablers, but only barely. I think you see what I’m getting at, but I’m also aware this is up for debate, as one of the criticisms I see about Cyberpunk 2077 is precisely that it lacks such side-activities and the city feels less lively as a result.

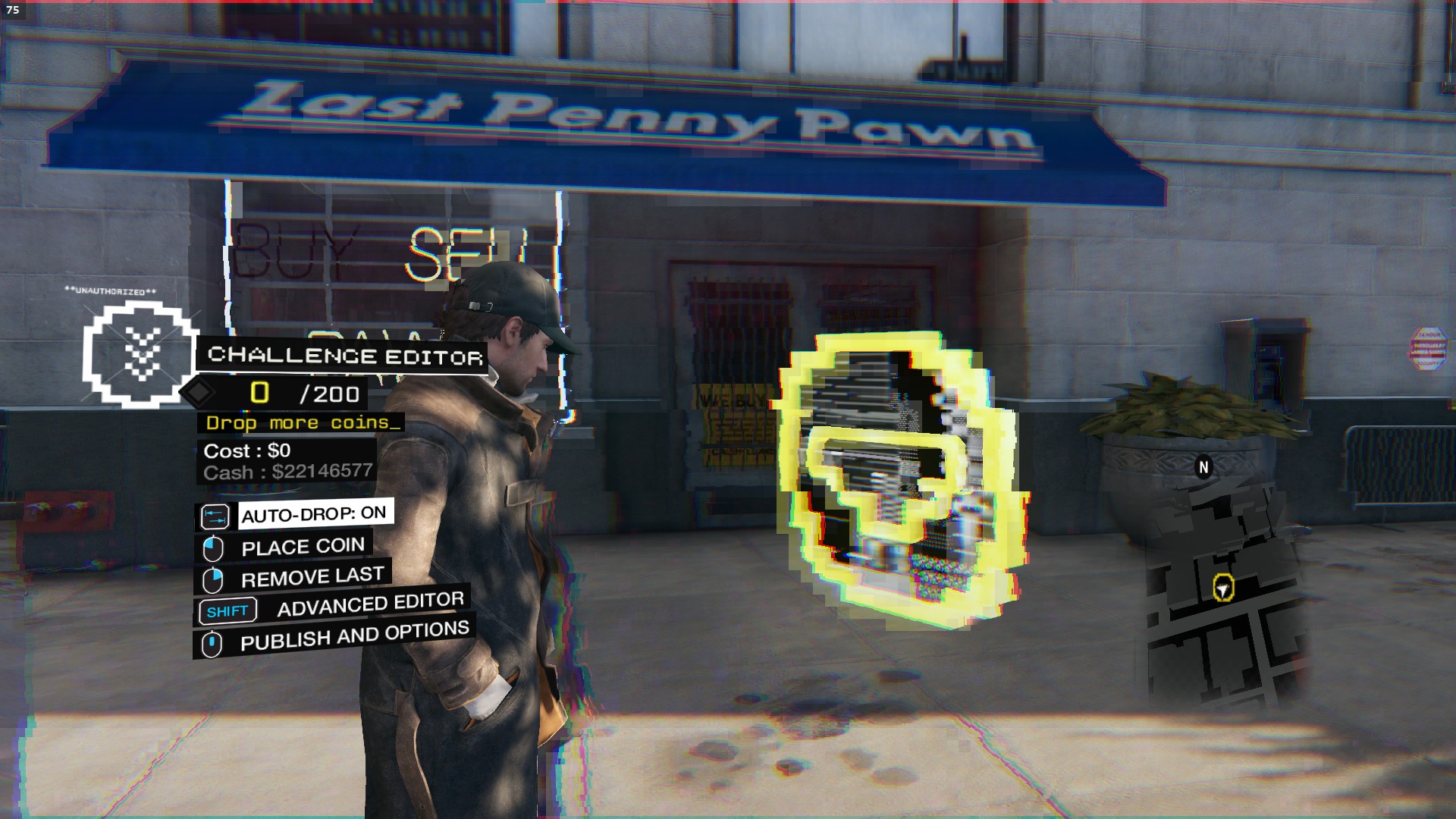

The “Augmented reality” Cash Run game is essentially a 3D platformer set within the game’s world; it mainly takes advantage of the normal parkour mechanics and its many levels are available as regular world locations outside of the game, sans the coins and enemies, of course. Cash Run has online leaderboards, and a separate “Cash Run Challenges” smartphone menu entry allows one to create their own levels and share them online. Other players have to purchase them with in-game money and you get in-game money for your sales; there’s even such a thing as trial versions of each challenge – it’s surprisingly fleshed-out, user-generated content buried relatively deep in the game! The custom challenges functionality can be abused to allow one to create their own teleport destinations anywhere in the world, as it instantly teleports you to the starting point of a challenge when you begin to edit it, and doesn’t teleport you back when you quit.

NVZN is the other AR game, and it’s basically a space invaders-themed shooter where the fictional enemies are overlaid in the game’s world; it can be played pretty much anywhere instead of being tied to physical level locations like Cash Run. It has online leaderboards too. NVZN is the sort of thing that would probably be really cool if you were playing it in real life, with something like a HoloLens coupled with hand tracking. However, the representation of such AR videogames inside another, regular, videogame that you’re just playing on a bog-standard 2D screen is… not that entertaining, except if you have a kink for inception. I don’t think I have played NVZN more than once. In a way, it exists more as a storytelling or worldbuilding device than as something most players are expected to visit more than a couple times; a means of saying “in this fictional universe, these sorts of AR games are feasible and common” – you can see NPCs playing NVZN at select locations, it isn’t one of Aiden’s special abilities.

Finally, there’s the “Digital Trips” minigames. These are themed as “out of this world” experiences, the implication is that they are the result of illicit drug use, and therefore one of the ways to launch them is through very legitimate street vendors present at totally not shady places. There are five of these game modes in total, and they are indeed the most “out there” of the bunch.

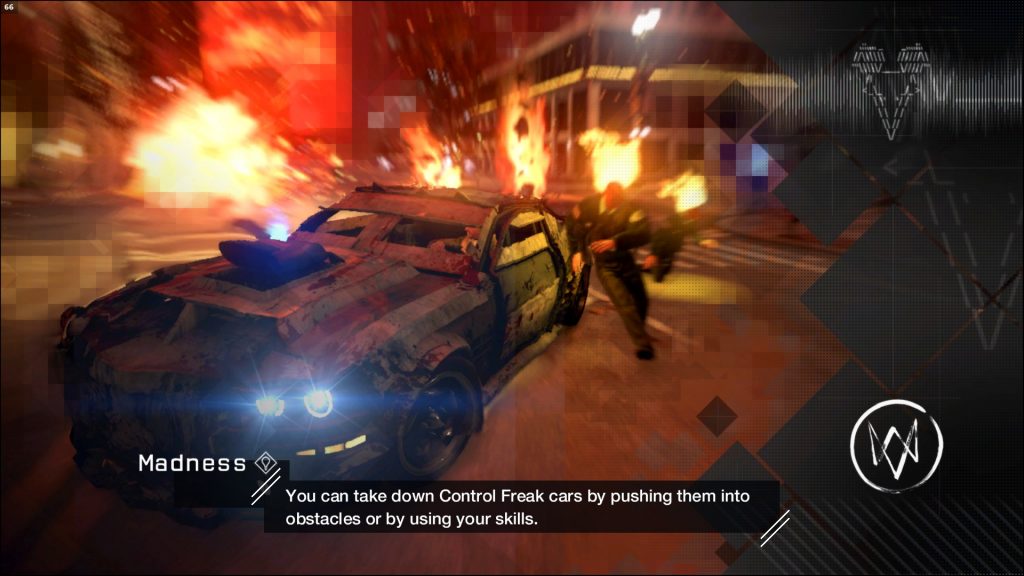

Some of the Digital Trips are worth thinking about for a bit. The “Madness” one (the one where you run over ever-spawning demons with a car) would probably have fit better in the cancelled Driver game that preceded WD1. In any case, the “digital trips” are a good showcase of the ability to repurpose a game’s open world; in a way, Ubisoft did what game modders sometimes do. I really am curious about how these minigames even came to be in the first place; neither “digital trips,” “AR games,” nor anything like them made a comeback in subsequent Watch Dogs titles. They were definitely memorable; just the other day, as WD1 was randomly mentioned in one of the most popular gaming subreddits, someone was mentioning how they felt the spider-tank minigame could have been a game of its own.

Each digital trip has their own loading screen and menu art, their own HUD style, their own soundtrack and SFX, and their own level system and skills tree. They provide radically different gameplay compared to the main game: for example, the spider tank one allows one to climb buildings (albeit in a limited section), and Madness is a refreshing change of pace from the reputation system in the main game that punishes you for running over pedestrians: there, the goal is precisely to do that. Much more effort and thought seems to have gone into these games-within-a-game than one might assume at first.

On their own, the widely different kinds of minigames represent a surprisingly big amount of content, that one might not expect when first picking up the game. I suppose these, and the “digital trips” game modes particularly, were the sort of luxury one can afford to implement when making the first game of a series, meaning there is still little data about how each new thing will be received by players and there is more of a willingness to introduce truly new things rather than iterate on the previous game’s formula. Subsequent titles in this series also introduce their fair share of “slightly tacked on” experimental things, but in my opinion none were as memorable, nor as disconnected from the main game, as the “digital trips” in WD1.

6. Vehicles

In WD1, you can drive cars, vans, trucks, motorbikes and boats. You can also ride the train, and there is a police helicopter, but neither of those are things you can drive yourself. Well, with mods, you can fly the helicopter, but I digress. There are different road vehicle classes, from slow ultra-compact cars, to sports cars, to utility vehicles, with varying “feel” and physics properties.

Vehicles can be obtained by taking any parked vehicle off the streets, stealing them from NPCs, or by spawning them using the “Car on demand” smartphone app. Boats can only be obtained by stealing them either from docks or other NPCs. In the app, vehicles are unlocked as one plays, and some need to be purchased with the in-game balance. Once a specific skill is obtained in the skills tree, stealing parked cars will “hack” them without alerting surrounding pedestrians or the authorities, instead of forcing Aiden to break and enter.

Even though certain vehicles can appear with different liveries and paint jobs, mainly depending on the faction they belong to, there are no vehicle customization or vehicle repair features available to the player. Vehicles have randomized license plates, in what is the greatest technical achievement since the great ’08 standardization of “Liberty City” license plates. 🤪

Vehicle physics and handling are one of the common criticisms of WD1. I must agree that they are far from great but, in a way, they are satisfying once you learn them. However, the learning curve is probably too steep for most casual players. You just can’t keep accelerating all the time if you want to take turns without constantly crash into things – just like what happened in GTA IV. The game doesn’t do a good job of informing players that turning is much easier if they use the Focus ability (the one that slows down time, and which is mapped to a keyboard/mouse button), and to be honest I am even unsure if this mechanic was intended: cars retain a much tighter turning circle for an instant even after disengaging Focus, which means you can engage it for just a couple frames, disengage, and take a sharp turn at normal game speed.

Because streets are often not that wide and contain a high density of vehicles, pedestrians and an assortment of fixtures and urban furniture, the fastest way to move around is using motorbikes. Bikes are also some of the best vehicles to take off-road. Funnily enough, in WD1, bikes only spawn parked, not in traffic, and I’m even unsure if there are AI-driven bikes in any circumstances.

Most cars do not feel particularly fast, contributing to the “fake world sizes” feeling. The game also doesn’t have many unimpeded, long road straights where one can easily put this to the test – even the wider motorways are full of vehicles. But when vehicle spawns are taken out of the equation or carefully controlled, as is the case in certain missions and in online races, movement definitely doesn’t feel too slow.

The vehicle sound effects are not especially good, certain ones like the drifting squealing sound needlessly artificial, others sound over-exaggerated or cartoonish – some smaller vehicles have excessively high-pitched engine noises, for example, that become tiring over time. This is a passable weakness for the first game in a series, but sadly this did not see much improvement in any of the subsequent games.

The vehicle damage model is adequate, similar to what is found in other open world games like Sleeping Dogs or Just Cause 3 and 4, but it isn’t on par with contemporary GTA titles. Vehicles that are very damaged begin to suffer issues like poor acceleration and slow gear shifting; those that get extremely damaged catch fire and eventually explode. Damage is not based on soft body physics: vehicles can break and even lose parts like doors and mirrors on impact, but the damage to these parts and the main body is based on a series of fixed states. Scratches and deformations will always appear similar within each bumper or body part, and not precisely dictated by how a collision actually occurred.

Vehicle damage is something GTA IV and V both do better, not to mention games focused on modeling such things, like Wreckfest or BeamNG. I feel that the comparatively simple damage model isn’t something that directly takes away from the enjoyment of the game, but certain fun sandbox scenarios never occur – who has never laughed at how bent, and yet still working, a friend’s car is in GTA Online? The vehicle damage model remained largely the same throughout the Watch Dogs series.

In many ways, the game’s vehicle physics are more appropriate for an open world arcade racing game in the style of The Crew or Forza Horizon. They are not particularly realistic, but they are involved, in the sense that the player must be engaged in the activity of driving, and they will find it frustrating if that’s not something they enjoy doing. It’s possible that, once again, WD1’s past life as a game in the Driver series is showing through. However, players – understandably – don’t come into WD1 expecting or desiring a racing game. WD1 is not strictly one, but when it is, it pulls it off relatively well. The developers certainly knew that, hence why there are “Fixer contracts” in the game, multiple chase sequences, a racing multiplayer mode and the aforementioned “Madness” minigame. WD1 attempts to hide it, but sometimes it is more of a driving game than it is a “hacking” one. Ubisoft must have realized this, and adjusted WD2 accordingly, as we’ll see on a future post.

7. Graphical quality (and some notes about irony and missed expectations)

Moving on, time to discuss graphical quality. I dove into WD1 not knowing about any of the controversy regarding the “graphics downgrade,” and therefore I also buried the subject in this sort of retrospective. Of course, my view is tainted, as I first played this game on PC, years after it released, with a GPU that was clearly more powerful than the minimum requirements for the PC version, and which runs the game on completely maxed settings without breaking a sweat. Remember: this game was released for the seventh generation of game consoles, that is, the PS3, the Xbox 360, and (although including it here as part of the 7th generation is “wrong” but not innocent…) the Wii U. I have seen screenshots and recorded gameplay of the game running on those consoles. The game genuinely looks worse than GTA V did on PS3/360. But I suppose the main problem, and which sparked the bad reception of this game, was that Ubisoft had put out some nice looking trailers which, well, were indeed really nice looking and over-represented how the game looked like at launch, even on PC.

The silly thing is that over the years, different modders have managed to make the PC game look pretty much like on the trailers, strictly by changing the game’s files, i.e. without any “out of engine” post-processing or graphics pipeline replacement tricks. The earliest and most popular mods pretty much just made everything look wet all the time, but years after those became popular, different people have made things look properly good while still supporting weather other than rain.

One can only wonder if this wasn’t another example of a game being downgraded to look less impressive on PC, just to not annoy the console makers and users too much; or maybe Ubisoft truly didn’t know what the GPUs of the eighth console generation would be able to deal with, and overestimated in their trailers. Much like Cyberpunk 2077, WD1 may have suffered a quality loss (and not just in the graphical department) to still support the then-previous generation of consoles, and much like Cyberpunk, it definitely over-promised and under-delivered… just not in as many aspects.

Both Cyberpunk and the Watch Dogs games feature narratives that are largely anti-corporations and/or anti-establishment, denouncing the evil of the “big corpos,” the erosion of personal freedoms and consumer rights, and the dangers of authoritarian regimes. There is a certain irony in that both series have a “sticking it up to the big man” theme, while their problems during development and reception end up being a good showcase of the issues that currently plague triple-A games, and which are related to the societal issues portrayed by their narratives. See also: the sexual misconduct scandal at the same company that released a DLC mission for WD2 centered around sexual misconduct. More on that on a later post…

Coming back to the graphics department to analyze the graphical quality of the released game, I must say that WD1 has stood the test of time relatively well, at least on PC, without any mods. It surely doesn’t look like a 2020 game, but it doesn’t look too dated. Eight years after release, it’s aging better than many other games have after the same amount of time, including for example the PC ports of GTA IV and Sleeping Dogs. Not that one can blame earlier games, to be honest, the last 5 or so years have certainly seen fewer GPU power leapfrogs, or at least, fewer accessible ones, than the 4-5 years before them – and also, fewer changes in 3D rendering techniques save for relatively recent and optional techniques like hardware-accelerated raytracing.

The graphical fidelity of GTA V’s world, a game that was considered the pinnacle of open world video game graphics for a good portion of the last decade, can still look better than WD1’s, in what I believe is largely due to more convincing bloom and fog effects. It’s important to note that the PC port of GTA V – what we’re comparing against – was released almost a full year after WD1. It enjoys a much wider selection of graphical options, including some that allow the game to take more advantage of current GPUs, like the ability to use higher level-of-detail assets at distances further away, and the ability to internally render frames at higher resolutions before scaling them down to the monitor’s resolution – something that in WD1 can only be achieved with external solutions like Nvidia DSR or DLDSR, with less convincing results. Ubisoft appeared to take notes, as WD2 would include a much more complete graphical settings menu including multiple “future-proofing” options.

In any case, I consider WD1 to be on the “later 2010s” side of the curve as far as looks go, and in my eyes, the thing that dates it the most is the human body appearance and also the quality of some textures when seen up close. Compared to games from the mid-2010s, skin, hair and motion fidelity are aspects where more recent games show notable improvements, and neither WD1, GTA V nor most other games of the era score high here; certain body features, notably the hair and NPC clothing, can look slightly better on GTA V than on WD1 – in the latter, many NPCs and their clothing can have a low-detail, almost wax-like appearance. NPC animations in WD1 can also look a bit dated and artificial, but in my opinion this is offset by the quality and variety of the animations for Aiden, surpassing that of many games, including GTA V. As for inconsistent texture quality, this is something that plagues many games, particularly (in my experience) open world ones, and unfortunately WD1 is no exception.

Out of all objects, vehicles have some of the best graphical quality in this game. In addition to the good reflection quality I pointed out above, cars even cast accurate headlight shadows, with two light sources, one per headlight! At the risk of sounding repetitive, I might need to bring Driver up again: would vehicles in this game have the same quality if the game’s development history had been different?

Even without mods, nights and rainy days in WD1 look beautiful and I’m told, by people who live or have been there, that they capture relatively well the looks of the windy city – unlike the geography of the world, which is an extremely creative adaptation, as I mentioned. But then again, said people are big fans of the game.

The different time and weather conditions allow WD1 to pull a very grim look when needed while still looking colorful at other times – it doesn’t have a “brown filter” on it like so many games from the decade before.

The style of the game’s UI/HUD is quite iconic and matches really well the tone and setting of the story, taking some inspiration from “Hollywood hacking” but not excessively. It can sometimes look a bit too busy, as I complained previously. The HUD has a very “rough” style, with text and icons often placed in solid color rectangles that are not rounded, and with some icons and fonts purposely having a low-resolution, aliased look to them. When text such as mission objectives appears in the HUD, it often comes in animated, with gibberish characters quickly cycling through at the end of each text string as it is revealed, in what is meant to represent a decryption process of sorts. This is mixed with some much cleaner-looking elements, such as the smartphone and shop menus, which feature full-color high-fidelity icons, smooth animations, rounded corners and no text decryption effects.

On PC, using modern screen resolutions (1080p and especially above) the different UI elements can appear larger than necessary. They also have really wide margins relative to the screen borders – the minimap, for example, could really be much more out of the way, like it is in WD2 or GTA IV and V. I assume this is a remnant from the PS3 and XBox 360 generation, where people playing on CRTs or older flat screens was a more common occurrence, and these often required quite generous “safe zones” around the edges of the picture. It is a shame that neither a setting for UI scale nor screen margins is present in the game. Somewhat related to this, the game also deals poorly with ultrawide aspect ratios, e.g. cutting off the top and bottom of the smartphone’s UI when playing in 21:9 – in general, it’s as if the game rendered everything in 16:9 and then cut off the top and bottom, so on ultrawide you actually get to see fewer things than if the game widened the cameras’ field of view, to compensate for the wider aspect ratio. I have a 21:9 monitor but captured all screenshots in 16:9 precisely because of this.

Style-wise, I don’t think anything in the HUD/UI department was groundbreaking even back then, and some of the interaction that happens through the “phone” could use some improvement – in a past section, I have mentioned how the division of options between the phone, map screen and pause menu could be improved, but you can generally get to all the information and options you need without too much effort or confusion. WD1 was not perfect and WD2 was even better in this regard, but this is one aspect where the most recent game in the series managed to take a turn for the worse, so I think it’s worth praising what wasn’t broken in earlier games and barely needed fixing.

On a final note about the HUD’s graphical properties, there are some possible annoyances that can be fixed with mods. The fact that the GPS route is drawn both on the minimap and in-world is a bit unnecessary – the minimap would suffice. And when targeted, hackable world elements like bridges and traffic lights are drawn with a sort of blinking highlight that is equally unnecessary, as the button prompt to hack them is sufficient indication that they are interactive and that you are targeting them.

8. Score and sound design

I’ve touched briefly on sound design aspects as I presented my opinion about vehicles and weapons, but as I did so, I was mostly focusing on specific sound effects. The overall sound design for UI elements and gameplay events is well thought-out and coherent with the popular culture notion of “hacking,” without being too much of a cliché. Individually, vehicle noises, weapon sounds and UI feedback one-shots, are not remarkable – but WD1 has you hear much more than just sound effects. The game’s original score was composed by Brian Reitzell, a name unknown to me and probably to you, but who is apparently a BAFTA nominee that has worked on multiple renowned film and TV soundtracks. Wikipedia also informs me that the score’s genre is krautrock.

In more subjective terms: the score is great! It fits very well the darker, tense story that the game tries to tell, and is very effective at setting the mood throughout the missions and while roaming through the game’s adaptation of windy city. Like in many other games, the score is scripted to react to what’s happening in the world and missions, and even in more mundane activities like navigating the map or the brief loading into a multiplayer session, there’s a very fitting, futuristic, “hackingesque” ambient noise present. In general, the score and UI feedback sound effects work well together.

On a less positive note, the licensed music, i.e. what would play in the car radio stations if this were a GTA title, felt to me as being B-grade. This should not be too surprising since licensing music for video games is extremely expensive and cumbersome, so much so that many prominent removals of games from sale, as well as post-release removal of tracks, are due to expiring music rights. Games like Sleeping Dogs did not have “chart hits” on their licensed music, either; GTA titles are really an exception in this regard. Most tracks in WD1’s “media player” are not memorable, variety feels insufficient, and I would even dare to say that many tracks don’t fit the mood of the story and the environments. Through all of my playthroughs, I ended up skipping many tracks or outright disabling the music. However, if ruining the mood of the missions is what you want, the licensed music does provide a striking contrast to the original score.

Players can listen to music at pretty much any point in the game by using the “music player” built into the smartphone. They can exclude tracks from the “playlist” so that they don’t play, but the interface is a bit clunky and painful to use. The game lacks one feature I love in GTA, which is the ability to play your own music files in-game. Then the “music player” would actually be useful regardless of the quality of the licensed tracks. Vehicles don’t have radios, but by default the player starts and stops play as you enter or leave a vehicle. Unfortunately, it doesn’t remember at what point of the track you were when you last paused the player, which means that if you enter a vehicle for two minutes, leave, and enter the same or other vehicle at a later point, you’ll listen to the same track as before, but from its start. This definitely contributes to a sense of insufficient variety in the included licensed music: if you’re not careful, you’ll be spending good portions of your play sessions just listening to the beginning of the same song. In the settings, it is possible to disable the automatic playing of music in cars.

9. Multiplayer

Time to talk about one of my favorite features of WD1: multiplayer. I’m going to describe this part of the game in more detail, because I suspect some players mostly ignored it, and also because this will be the first component to get lost to time. Throughout the writing of this post, as has been happening over the last few years, WD1 multiplayer modes were not always available. For example, around February or March of this year, the matchmaking was disabled, possibly as part of the aftermath of one of the many cyber-attacks targeting Ubisoft, and it was unclear whether they would come back. More recently, Ubisoft has announced that they are shutting down the servers for a variety of their titles, even leading to some single-player DLC no longer being playable at all, which has resulted in some public outcry and a multitude of opinion pieces about consumer rights on digital purchases. While the Watch Dogs series seems presently unaffected, as long as Ubisoft continues down this path, it’s inevitable that the matchmaking service for WD1 will be shut down one day.

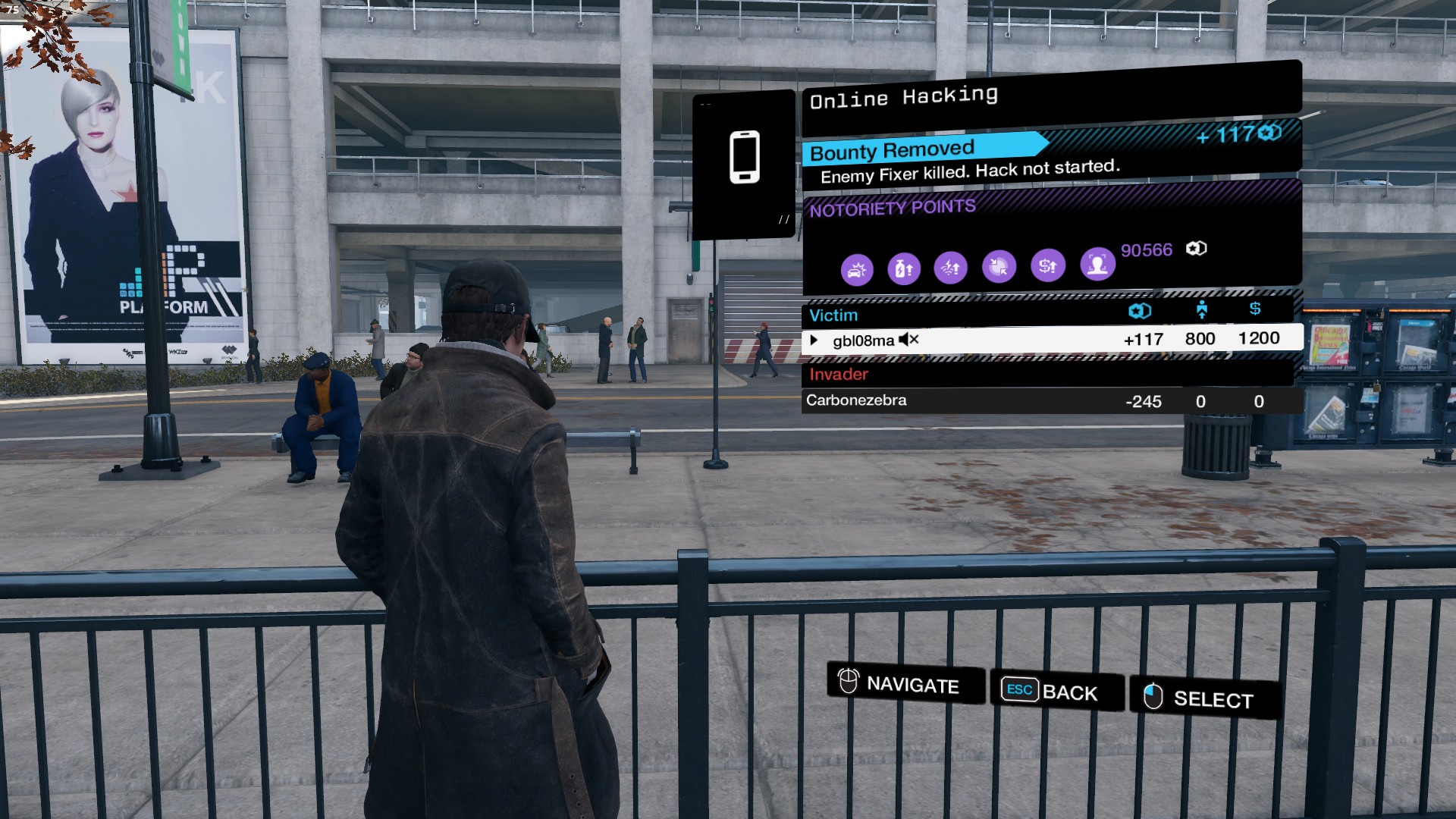

At launch, the game featured six multiplayer modes, accessible from within the normal game and playable interchangeably with single-player content, without interrupting the local playing session, i.e. without going back to the main menu.

All multiplayer modes share a main scoring system, a single number tied to your account: the “online notoriety,” which you can earn and lose depending on how well or poorly you do in the different online modes. You typically earn points when you or your team wins a match, and lose when you don’t, but if I remember correctly, in rare cases you can lose points even if you win but perform poorly within your team. It’s definitely not the most fair or understandable scoring system, and looking back, I’d say you’ll enjoy the game more if you attempt to completely ignore it. Just pretend that purple number in the bottom right isn’t ther— not so fast, because some skills are tied to the notoriety level, and to have them all available, you need to keep the notoriety above 12500 points. But other than that, I’d say one would have a better time by not focusing too much on this number.

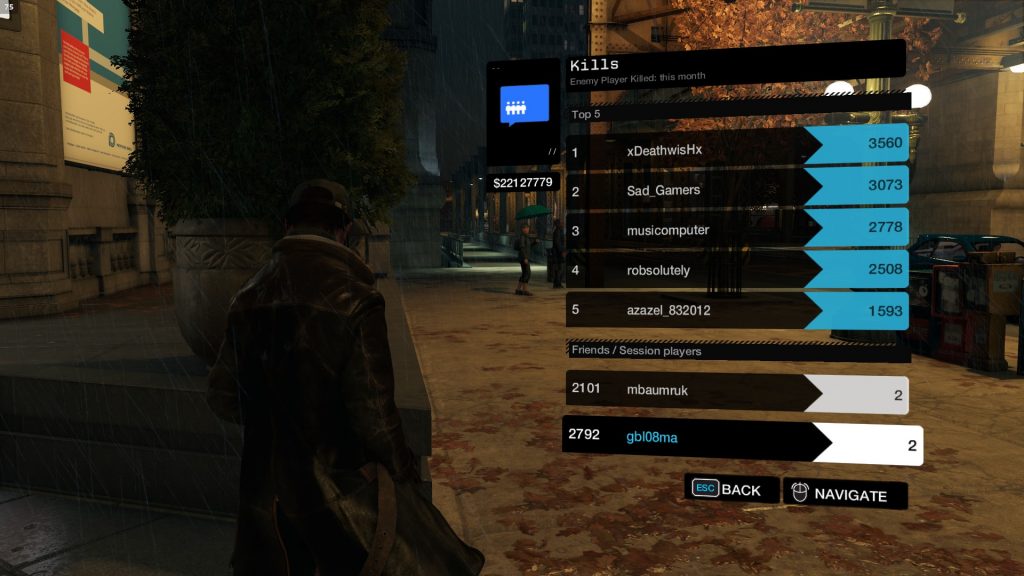

In addition to the singular “online notoriety,” the game also has leaderboards specific to each mode buried in the smartphone; I think most players have never even looked at these, and yes, of course the data in them doesn’t seem to be very consistent: there are definitely many “impossible” records in there. There are leaderboards for some minigames as well.

For all modes, the only communication option is voice chat, which features terrible quality and which I disabled less than one minute after discovering its existence; to make matters worse, it comes enabled by default, without push-to-talk, so you’re bound to hear plenty of noise and random conversations from people who don’t even know it exists or that it can be disabled. Fun, and very dystopian, keeping with the theme of the game! (And yes, Ubisoft kept this fine idea in WD2!)

On the technical side of things, multiplayer is fully peer-to-peer with the only servers being the matchmaking/leaderboard ones – as was typical of multiplayer solutions in games alike, at the time at least. This means that anyone can see the IP addresses of those they are playing with, like in GTA Online. One of the players is automatically selected as the host, and when they leave the online session, the whole game stops for a couple seconds as a new host is selected – fun, and totally doesn’t mess you up in the middle of fast-paced action! Yes, there are cheaters, but all in all, things remained playable for a surprising amount of time, and as far as I could tell, still mostly are (I haven’t really played a lot recently, but I suspect even the cheaters have mostly lost interest). I might eventually write a blog post just about cheating and cheaters in WD1, and how vigilante modders (heh) eventually tried to take care of the most egregious of said cheaters.

I said the game initially featured six online modes. For some years now, it has only featured five: one of the modes was a “ctOS challenge mode” where the player playing the game proper had to finish a checkpoint race, playing against someone on the “ctOS Mobile App” who would use the different hacking opportunities in the open world (bridges, steampipes, traffic lights, etc.) to slow the racer down and wreck them. The app is available for iOS and Android if you have a time machine that can go back to 2017, the year it was removed from app stores and its online component shot down. I managed to play at least one match in this mode, as the racer, before it became unavailable; I didn’t find it too interesting and I felt that anyone with sufficiently good driving skills in the game would always beat the mobile player, essentially turning the mode into a guaranteed win factory – or maybe my opponent at the time was just really weak.

Fortunately, the “ctOS Mobile App” kind of companion app did not make a comeback in any subsequent Watch Dogs game, and I hope that kind of game companion apps that inevitably get unmaintained and abandoned was a fad restricted to that period around the release of GTA V and WD1. The Division, another Ubisoft game released in 2016, was to have such an app at first, but released without one.